Blog

The Price Is Wrong: Limiting D&O Exposure at Class Certification

| In this week’s D&O Notebook, my colleague Walker Newell explains a significant recent court decision that provides companies with new tools to defeat securities class actions—at least, in theory. He also walks through the decision’s potential implications for public company disclosure practices, securities plaintiffs’ case selection practices, and the D&O insurance environment. – Priya Huskins |

In federal securities class action litigation, the motion to dismiss is typically the main event, and class certification is something of a backwater. But earlier this year, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals wrote a significant opinion with implications for both class certification and motion to dismiss practice. I’ll cut through the legalese to unpack the decision and suggest how companies and insurers should be thinking about the future securities litigation risk landscape.

The Motion to Dismiss: An Eight-Figure Coin Flip

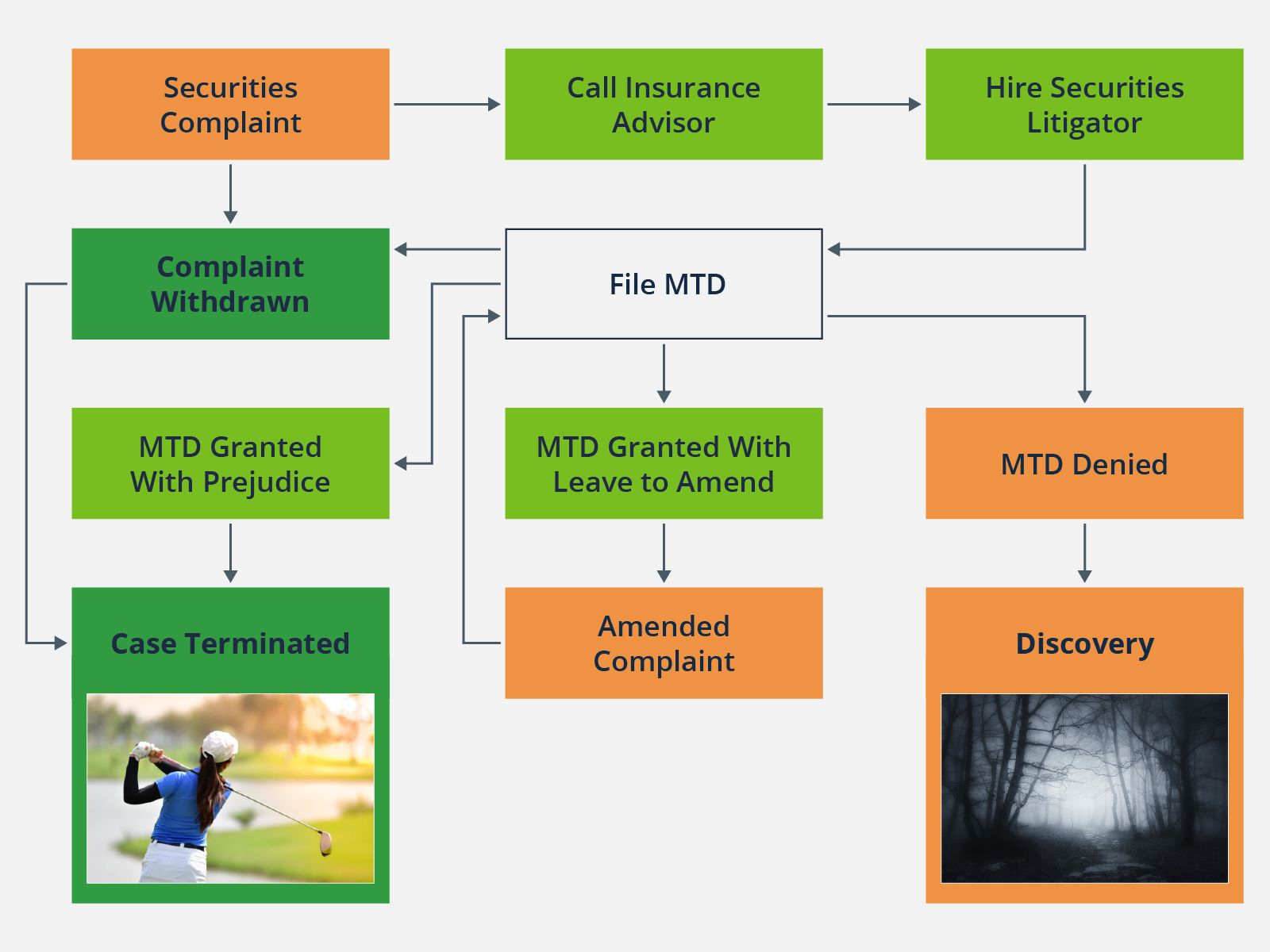

If your public company is served with a securities class action complaint, your first step will be to call your trusted insurance advisor to notice the claim and determine what constraints, if any, your D&O insurance policy imposes on your choice of defense counsel.

Your next step will be to hire highly competent and experienced defense counsel. Once your defense counsel is on board, they will often be single-mindedly focused on one thing: winning your motion to dismiss.

More than anything else, the motion to dismiss stage drives outcomes in federal securities class action litigation. A motion to dismiss is filed in about 96% of cases. If a case is dismissed with prejudice, you are out of the woods and will have more time for golf. If a case survives the motion to dismiss stage, you remain in a thicket and the odds of a settlement (average: $25 million1) go up substantially. This isn’t particularly complicated, but I like flowcharts, so here’s a flowchart.

Over the past decade, the courts have dismissed roughly 42%2 of all securities class actions. Another 15% were withdrawn by plaintiffs. A whopping 0.1% went to trial. The other 43%? They all settled.

Class Certification: A Low Percentage Bet

Class certification is another significant stage of securities class action litigation—in theory. But while a class certification motion can serve as a wedge for settlement discussions, it is rarely a successful way to get a securities class action thrown out of court. I’ve already used up my per-blog chart allocation, so here are some bullets (courtesy of NERA) to keep you reading:

- Last year, a motion for class certification was filed in only 17% of resolved cases.

- Of these, about 7% settled before the class certification motion was resolved.

- Of the remaining 10%, a class was certified in almost nine out of 10 cases.

This all adds up to a less than 2% chance that class certification will be the key that solves your securities class action puzzle. Have recent developments changed this calculus? Let’s find out.

Class Certification: The Basic-s

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 (“Rule 23”) allows individual plaintiffs to band together as a class. To comply with Rule 23, federal securities complaints must include class allegations. In a securities class action complaint, class allegations are effectively boilerplate, and they are not typically at issue during the motion to dismiss stage. If a case survives the motion to dismiss, discovery begins and the court will set a schedule for class certification.

If there is no settlement, certification must take place before a case can continue to a class-wide trial. Again, historically, defendants have faced long odds against defeating a motion for class certification. Given this, it is not uncommon for defendants to stipulate (i.e., agree) to class certification. (Some judges may even encourage the parties to agree to not waste the court’s time fighting about this.)

In the rare cases where a class certification motion is decided on the merits, plaintiffs must show that they relied on the defendant’s supposedly false statements. How does this work in class cases involving publicly traded securities, where there are thousands or millions of shareholders buying and selling shares for various reasons?

To answer that question, we need to go back 35 years, to 1988. It was a big year. Two of the best Christmas movies of all time—Scrooged and Die Hard—were released in theaters. The Iron Curtain started to fall. “Push It” by Salt-N-Pepa reached #19 on the Billboard charts. And the US Supreme Court decided Basic v. Levinson, one of the canonical federal securities cases.

In Basic, the Supreme Court held that securities class action plaintiffs can invoke a presumption of reliance—and survive the class certification stage—by invoking the “fraud-on-the-market” theory. The theory goes something like this:

- Our public securities markets determine pricing efficiently and promptly based on publicly available material information.

- A public company’s stock price reflects the market’s perceived impact of all publicly available material information.

- If a company makes a material false statement but the market doesn’t know it is false at the time it is made, the market will misprice the company’s stock.

- When the market learns the company’s past statement was false and that information is material, the company’s stock price will fall because the market is highly efficient (see #1–#3, above).

- It is fair and reasonable for the courts to presume that securities class plaintiffs are relying on any publicly available material false statements baked into the efficient market price at the time they buy the company’s securities.

To pass the Basic test at class certification, plaintiffs have to show that the alleged misrepresentation was publicly known and made in an efficient market, and that they traded at relevant times. Historically, this has not been a problem for plaintiffs, as demonstrated by the very low rate of defense success at class certification.

Price Impact Rebuttal and Goldman

But Basic left an Easter egg for future defendants: The Supreme Court made the presumption of reliance rebuttable. This meant that defendants could still theoretically disprove reliance—and beat class certification—by proving that the market was not efficient. But, to put it mildly, this has not been a fruitful strategy for defendants since Basic was decided: 2013 research by Stanford Professor Joseph A. Grundfest found only five instances in which defendants successfully rebutted the presumption.

However, in 2014, the Supreme Court opened a new door for defendants to rebut the presumption of reliance by showing that the supposedly false statements underpinning a securities fraud claim did not actually impact the company’s stock price. Over the next decade, the courts have tried to figure out how to apply this new test, and the Supreme Court has also weighed in to clarify on a couple more occasions. Most recently, in August 2023, the Second Circuit wrote a detailed opinion decertifying a class in a long-running securities case (which also involved an earlier Supreme Court opinion) against Goldman Sachs (collectively, Goldman).

I’m not going to summarize the Goldman cases in detail (for a good explainer, check out this Cooley article). The legal contortions in judicial opinions don’t really matter to your business. You want to know: What does it mean? Why does it matter?

Not all supposedly false statements impact a company’s stock price. If a statement had no impact on a company’s stock price, is it reasonable to presume that thousands of differently-situated investors all “relied” on the statement in a material way? Stripped down to the bones, Goldman provides a roadmap for you to prove that investors did not rely on supposedly false statements by showing that those statements did not impact your stock price and—potentially—to get your securities class action kicked out at class certification. Remember that securities fraud cases involve two types of statements:

- Initial false statements that caused the stock price to increase or false statements that allowed an improperly inflated stock price to stay high (“price inflation statements”).

- Later statements telling the world that something bad has happened and causing “the truth to be revealed” about the earlier false statements (“corrective disclosures”).

With this framework in mind, to win at class certification under Goldman, you need to show that:

- The price inflation statements were “generic.”

- There was a “mismatch” between the price inflation statements and the corrective disclosure.

Looking at the disclosures at issue in Goldman provides a better sense of what this means:

- The key alleged price inflation statement: “We have extensive procedures and controls that are designed to identify and address conflicts of interest, including those designed to prevent the improper sharing of information among our businesses.”

- The key corrective disclosure: An announcement that Goldman had settled a case with the SEC related to a specific conflict of interest.

The two disclosures at issue related to the same subject but were not mirror images, and the price inflation statement was fairly non-specific. Confronted with this setup, the court decided that there wasn’t enough connectivity between the two statements and decertified the class.

Going forward, this will be a heavily case-specific analysis, subject to the vagaries of judicial decision-making. But the basic takeaways are:

- The more generalized the price inflating statement, the better chance defendants will have of defeating class certification.

- The greater the substantive distance between the price inflating statement and the corrective disclosure, the better chance defendants will have of defeating class certification.

- If the price inflating statement is specifically mentioned, admitted to be false, or otherwise at issue in the corrective disclosure, defendants are probably not going to defeat class certification.

Disclosure Implications

Goldman is obviously a good case for defendants. Will it have a huge impact? Only time will tell. Here are some potential implications for public company disclosures and securities litigation:

- Many securities class actions are filed after public companies disclose regulatory issues. But having a non-securities regulatory issue and a corresponding stock drop does not mean you have committed securities fraud. The natural conclusion from Goldman is that if you can keep your disclosures about legal and regulatory compliance relatively generalized—while, of course, complying with your disclosure obligations—you will be better positioned to defeat a class action if specific problems arise later.

- In Goldman, the Supreme Court and Second Circuit pointedly observed that there is a ton of overlap between price impact analysis at class certification and the question of materiality, which is often litigated at the motion to dismiss stage. At the motion to dismiss stage, courts often grapple with the question of whether generalized statements are sufficiently meaningful to a reasonable investor to be material. While it was not directly applicable to the motion to dismiss stage, the Second Circuit’s critique of generic statements could still prove influential to district courts deciding materiality.

- Traditionally, the most attractive cases for plaintiffs are big stock drops for large cap companies. If a case meets these criteria but plaintiffs have only a very generic price inflating statement that does not match the corrective disclosure, what will they do? Over time and if this analysis is adopted by other circuit courts, sophisticated plaintiffs’ counsel may increasingly try to pick cases where they can identify relatively specific price inflating disclosures and where there is a relatively close match between front-end false statements and corrective disclosures.

D&O Insurance Implications

If you’ve made it this far, you must be eager to hear about Goldman’s implications for the D&O insurance market. Unlike Zoltar, the magic carnival machine from Tom Hanks’ Big (also released in 1988—what a year!), I can’t predict or influence the future. But I have two prognostications, one little picture and one big picture.

Little picture, Goldman underscores the importance of event study coverage in your D&O policy. To bring a viable price impact defense, you will need experts to prepare event studies. In an event study, an expert economist evaluates a variety of metrics and opines that the relevant disclosures did not have a statistically significant impact on the company’s stock price. In Goldman, the Second Circuit discussed the defendant’s expert reports at length and, among other things, found it significant that expert analysis of hundreds of analyst reports did not identify a single reference to the price inflating statements. An endorsement to your D&O policy that provides event study coverage may be available in the market; talk to your trusted insurance advisor.

Big picture, if other courts follow Goldman and begin to deny motions for class certification more frequently, insurance carriers might begin to have more of an appetite to challenge class certification. The magnitude of class action settlements could possibly be impacted, with downstream impacts on D&O premiums. On the other hand, until more data trickles in, fighting on class certification will still look like a costly and low percentage bet, particularly if palatable settlements are available at earlier stages of litigation. While it’s likely that defendants will have relatively improved outcomes at class certification, it will be years before we know the true effect of these price impact cases.

1Woodruff Sawyer D&O Databox™

2Woodruff Sawyer D&O Databox™

Author

Table of Contents