Blog

FCPA: What’s the Big Deal?

Are you a multi-national company that’s headquartered in the U.S.? Are you well equipped for what may happen if something you’ve done is considered bribery domestically and abroad?

The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 (FCPA) is enforced by both the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. It’s applicable both to public and to private companies. And that’s just the start when it comes to anti-bribery rules and enforcement. Almost every country has its own version of anti-bribery rules, making the issue of anti-bribery a very big deal for corporations doing business abroad.

As a refresher, FCPA has two sets of provisions: anti-bribery and bookkeeping. The anti-bribery rules prohibit the bribery of public officials of other countries. These provisions forbid individuals and companies from attempting to wrongfully influence an official by authorizing payment or anything of value – directly or indirectly – to obtain or retain business.

The FCPA’s rules on bookkeeping are also very strict. They forbid the use of any trickery designed to conceal the fact that bribes are being paid. These rules are particularly tricky for individuals who “should have known” that something was wrong (i.e., engaged in willful blindness), especially for folks who set up and are responsible for internal controls.

The FCPA rules on bribery apply to the following people and corporations:

- U.S. companies, public and private

- Most foreign subsidiaries of U.S. companies

- Foreign private issuers listed in the U.S.

- U.S. citizens and resident aliens

- Foreign nationals acting for a U.S. company

- Foreign nationals who commit an act in furtherance of a foreign bribe while in the U.S.

The act of bribing to obtain or retain business can include—but is not limited to—any of the following:

- Avoiding contract termination

- Avoiding duties or reducing tariffs

- Circumventing product importation rules

- Evading taxes or penalties

- Gaining access to non-public tender information

- Influencing enforcement actions or lawsuit adjudication

- Influencing the procurement process

- Obtaining improper advantage

- Obtaining regulatory approval

- Reducing taxes

Because it relates to bribing a non-U.S. government official, it’s important to understand what constitutes a government official. Here are some guidelines:

- All branches of a foreign government

- All foreign government entities and instrumentalities

- Public international organizations (e.g., United Nations, World Bank, International Monetary Fund)

- State-owned enterprises (“SOE”), such as airlines, hospitals, oil companies, and their officers and employees

- Political parties and party officials

- Candidates for public office

- Any “instrumentality” of a foreign government

It does not matter whether the foreign official is paid or unpaid, holds an “official” state post, or is a high-ranking or low-level administrative clerk. So when in doubt, treat all people in foreign countries as foreign officials.

One example of where this approach would have come in handy is the United States v. Joel Esquenazi and Carlos Rodriguez case. The defendants were convicted of bribing employees of a telecommunications company in Haiti (Les Telecommunications d'Haiti S.A.M. – “Teleco”).

The defendants argued that bribing employees of Teleco was not an FCPA violation. However, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit determined the employees in question were government officials because the government owned nearly 100 percent of Teleco, making it an “instrumentality” of the government.

The rules of what constitute a bribe under FCPA are strict, and include anything of value. The offer doesn’t even have to directly benefit the government official. Some examples include:

- Cash

- Charitable donations or social contributions

- Discounts on products and services not readily available to the public

- Entertainment, including meals

- Gifts

- Offers of employment to a foreign official or a relative of a foreign official

- Loans at favorable interest rates

- Payment or reimbursement of travel expenses

- Personal favors

- Promises or assumptions to pay or forgive debt

- Scholarships to a relative of non-U.S. government official

Keep in mind that depending on which country you’re doing business in, you’ll also have to comply with that country’s anti-bribery rules as well.

For example, while FCPA allows exceptions such as facilitation payments made to secure the performance of routine government actions like mail pickup and delivery, the UK's Bribery Act does not make any such exception.

Rather, the UK makes it clear that “facilitation payments, which are payments to induce officials to perform routine functions they are otherwise obligated to perform, are bribes.” In this way, the UK Bribery Act is stricter than the FCPA.

Part of preparing for these nuances is understanding the laws globally. There are a number of useful portals that will provide a lot of useful information as a starting point. Of course, you will want to consult with your trusted outside counsel for up-to-date specifics.

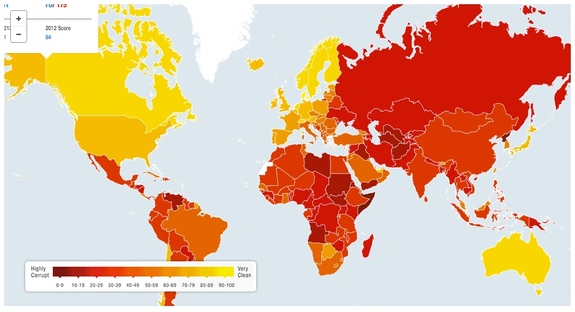

The following heat map image illustrates the 2014 "Corruption Perceptions Index" by Transparency International, which ranks countries and territories based on how corrupt their public sector is perceived to be. Yellow indicates less perception of corruption, whereas red indicates more.

To better understand your risk as a company, take stock of the countries in which you are operating, the trends in corruption there, and the anti-bribery laws. Then, you can begin to prioritize where the highest risk may lie, and start training your employees on how to avoid actions that could be construed as bribery.

Next week, we’ll take a closer look at the current trends when it comes to FCPA enforcement as Part 2 of this topical discussion.

The views expressed in this blog are solely those of the author. This blog should not be taken as insurance or legal advice for your particular situation. Questions? Comments? Concerns? Email: phuskins@woodruffsawyer.com.