Blog

SCOTUS on Securities: Waiting for NVIDIA

In private securities class actions, the motion to dismiss is critical. A victory can mean a quick and relatively inexpensive conclusion to litigation. A loss can mean many months of expensive and intrusive discovery. This week, my colleague and securities litigator Walker Newell unpacks a significant case currently in front of the Supreme Court that could hurt or help companies, directors, and officers when trying to get securities class actions dismissed. He also explains the implications that the case could have on D&O insurance markets. – Priya Huskins

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) chooses its spots carefully. It typically only chooses to hear about 100–150 of the roughly 5,000–7,000 cases that it’s asked to review each year.

The United States legal system is huge, and SCOTUS is the court of last resort. There is a lot to do, so it’s relatively rare for SCOTUS to weigh in on significant securities cases. This term, though, SCOTUS will be giving a gift that only a securities lawyer could love: An opinion on litigation brought by NVIDIA shareholders that may significantly impact the ability of companies to defend against private securities class actions. In this article, I’ll explain the stakes and what the upcoming opinion could mean for D&O insurance.

The Main Event: The Motion to Dismiss

Before digging into the SCOTUS case, a quick refresher on the motion to dismiss. It’s hard to overstate the impact of the motion to dismiss on outcomes in federal securities class actions.

| As I have explained in the past: |

|

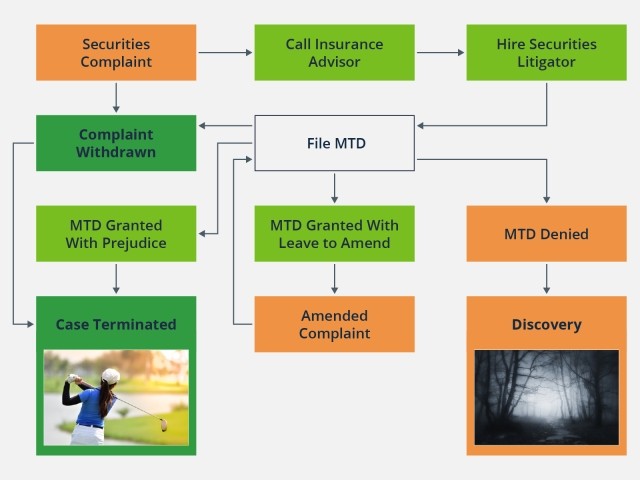

More than anything else, the motion to dismiss stage drives outcomes in federal securities class action litigation. A motion to dismiss is filed in about 96% of cases. If a case is dismissed with prejudice, you are out of the woods and will have more time for golf. If a case survives the motion to dismiss stage, you remain in a thicket and the odds of a settlement (average: $25 million) go up substantially. This isn’t particularly complicated, but I like flowcharts, so here’s a flowchart.

Over the past decade, the courts have dismissed roughly 42% of all securities class actions. Another 15% were withdrawn by plaintiffs. A whopping 0.1% went to trial. The other 43%? They all settled. |

Legal rules that give shareholder plaintiffs a better chance of getting past the motion to dismiss stage should tend to:

- Drive more settlements of securities class actions

- Over a period of years, contribute to greater losses for D&O insurance carriers

- Potentially drive D&O insurance prices up and/or constrict the scope of coverage

Legal rules that give defendants (i.e., companies, directors, and officers) a better chance of getting cases thrown out at the motion to dismiss stage should tend to:

- Drive more dismissals and fewer settlements of securities class actions

- Over a period of years, contribute to fewer losses for D&O insurance carriers

- Potentially drive D&O insurance prices down and/or expand the scope of coverage

The PSLRA Pleading Standard

As our readers know, the United States legal system stacks the deck in favor of plaintiffs in the early stages of civil litigation. Allegations in a complaint are given the benefit of the doubt: The judge has to treat them as though they were proven and true when deciding the motion to dismiss, even if a trial might later reveal the allegations to be bunk in the cold light of day and a full evidentiary record.

This paradigm, however, is tweaked in the context of federal securities fraud claims, which require plaintiffs to make stronger allegations on falsity and defendants’ intent (also called “scienter”) to get past the motion to dismiss stage. These requirements were put in place by the Private Securities Litigation Act of 1995 (PSLRA) to disincentivize plaintiffs trying to squeeze companies by getting into expensive discovery with weak claims. Importantly, under the PSLRA, discovery is stayed until the motion to dismiss has been resolved.

On scienter, under the PSLRA as subsequently interpreted by SCOTUS, a court first accepts “all factual allegations in the complaint as true.” Then the court determines “whether all of the facts alleged, taken collectively, give rise to a strong inference of scienter.” A “strong inference” of scienter requires an inference that is “cogent and at least as compelling as any opposing inference of nonfraudulent intent.”

To meet the PSLRA’s falsity standard, a plaintiff needs to “specify each statement alleged to have been misleading, the reason or reasons why the statement is misleading, and, if an allegation regarding the statement or omission is made on information and belief, the complaint shall state with particularity all facts on which that belief is formed.” 15 U.S.C. § 78u-4(b)(1).

Federal district courts routinely do battle with these mushy concepts when deciding whether or not to let securities class actions past the motion to dismiss stage. Creative plaintiffs’ lawyers try to find new ways to meet the pleading burden. Defendants try to convince courts that these new ways to meet the pleading burden are inconsistent with the PSLRA and past appellate court decisions. And the tug-of-war continues.

The NVIDIA Case

Earlier this year, SCOTUS agreed to hear a securities class action appeal involving NVIDIA that could have a significant impact on the future of these falsity and scienter pleading standards. The oral argument is next week, with a decision to follow in the coming months.

The appeal presents two questions for review:

- Whether plaintiffs seeking to allege scienter under the PSLRA based on allegations about internal company documents must plead with particularity the contents of those documents.

- Whether plaintiffs can satisfy the PSLRA’s falsity requirement by relying on an expert opinion to substitute for particularized allegations of fact.

On the scienter question, the NVIDIA shareholders argue that it’s unfair and inconsistent with the PSLRA to require them to specify the contents of internal documents on which they are relying to plead scienter. Instead, they think plaintiffs should be allowed to say something like: “We allege, based on information and belief, that internal company documents available to the CEO showed that the company would miss its number.”

| This excerpt from the shareholders’ brief is illuminating: |

| Confidential company documents are the one thing that plaintiffs are least likely to have in their possession at the start of a case, and thus the one thing that they are most likely to need to plead ‘on information and belief’—something the statute expressly permits. |

| NVIDIA and its lawyers see things differently: |

| A plaintiff who chooses to rely on this method of proving scienter cannot satisfy the PSLRA without alleging the contents of the internal documents in question. Otherwise, the allegations are not particularized because they lack an essential element of particularity: what the documents say. Put simply, allegations that a defendant reviewed certain documents cannot support an inference of scienter unless the contents of those documents contradicted the defendant’s subsequent statements. |

The briefs also include a lively debate on whether expert opinions can contribute to a court’s analysis of falsity at the pleading stage. NVIDIA says this would be an improper end run around the PSLRA, allowing plaintiffs to substitute “junk science” for the rigorous falsity pleading requirements that the statute demands. Shareholders, of course, disagree, arguing that expert reports can contain “factual matter.”

As the shareholders pointed out in the briefing, it is rare for plaintiffs to have access to key internal documents at the pleading stage of litigation. It can also be difficult to allege falsity at the motion to dismiss stage.

In civil litigation, this is what the discovery process is meant to do: If a plaintiff can make a bare minimum showing that a case has plausible legs, the judge is supposed to let them hunt from the smoking gun documents. The inherent tension here is that if plaintiffs are allowed to engage in pleading games that make weak cases look plausible, they can draw defendants into expensive and taxing discovery and drive settlements in non-righteous cases. Hence, the PSLRA’s more rigorous pleading standards.

In a divided court that often decides cases along ideological battle lines, the justices sometimes take solace in joining merrily together in less politically charged areas. There is, theoretically, support on both sides of the aisle for suppressing weak securities litigation. While the shareholders in the NVIDIA case have some solid arguments, if I were a betting man, I would probably place my money on the company’s side in front of SCOTUS. The oral argument next week should provide some initial indications of which way the judicial winds are blowing.

Potential D&O Insurance Implications

What impact will the decision have on D&O insurance? At a high level, anything that materially tips the scale in favor of plaintiffs or defendants at the motion to dismiss stage in securities cases has the potential to impact D&O insurance markets in the future. More cases in discovery mean more settlements. More cases dismissed before discovery mean fewer settlements. Over a long enough time horizon, these outcomes will translate into either higher or lower losses for carriers, affecting their risk appetite and approach to underwriting.

Today, the D&O marketplace for public companies continues to be dominated by supply and demand considerations, as an influx of new underwriters has driven prices down significantly from the 2021 peak. As we explained in Woodruff Sawyer’s Looking Ahead Guide: D&O Considerations for 2025, however, rate decreases are expected to continue to moderate. Broader trends in the securities litigation environment—increased filings, high settlement activity—have the potential to contribute to a more challenging D&O environment in the coming years. Depending on SCOTUS’s stance, the NVIDIA case could moderate or compound these trends.

Author

Table of Contents