Blog

Unicorns, Down Rounds, and Independent Directors

It’s 2016, and frankly, people are concerned about the valuations of venture-backed private companies. More than 140 “unicorns” exist today–private companies that have been valued at more than $1 billion.

People are uneasy because the headlines have been peppered with news of investors like Fidelity Investments marking down the value of their investments in popular, privately held startups.

It’s never fun when valuation bubbles burst, or even just gently deflate. Those of us who have been in Silicon Valley long enough see the signs for an upcoming rash of down round financings for some private companies, unicorns or otherwise.

(As a reminder, people often expect that every future round of private financing for a company will be at a higher valuation than the last. When that’s not the case, it's called a down round of financing.)

By their nature, down rounds normally result in diluting the position of existing shareholders. Some may be completely washed out.

As a company’s prospects diminish, investors’ patience may also shrink; rather than continuing to support the company, they may decide that the better choice is to sell the company before all of its “inflated” value has drained away, whether due to the company’s failure to execute or a general market correction.

Unicorpses piling up?

With more unicorns stumbling, investors are getting nervous. As one New York Times author points out in her article:

The odds that the unicorns will all reap riches if they are sold or go public are slim. Over the last five years, at least 22 companies backed by venture capital sold for the same amount as or less than what they had raised from investors, according to a data company, Mattermark. This means investors did not reap many returns — but there was even less left over for employees. Last year, the flash sale company Ideeli was sold to Groupon for $43 million after raising $107 million from investors. Fisker Automotive, the maker of hybrid electric vehicles, sold for $149 million after raising more than $1 billion.

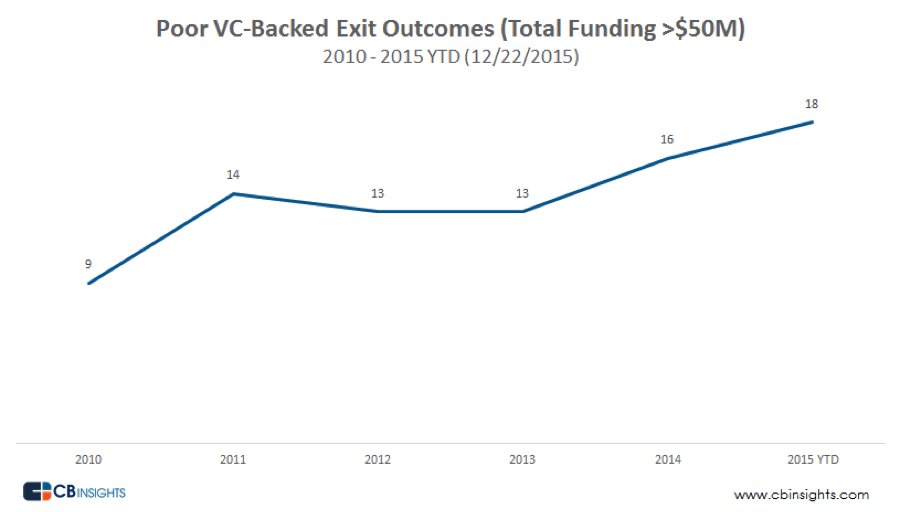

CB Insights’ analysis found that since 2010 a rising number of companies had exits that were lower than the total amount the company had raised in private rounds of financings:

Shareholders invest with the expectation that a board of directors will put the shareholder’s best interests first when it comes to making important business decisions. They also expect a positive return on their investment, but not every company has a happy ending.

When Valuations Go the Wrong Way

In November 2015, Good Technology, a mobile security startup on its way to going public and once valued at $1 billion, sold to BlackBerry for $425 million.

This reversal of fortune meant that the common shareholders – many of whom were current employees – saw the value of their stock plummet from $4.32 per share (a valuation from earlier in 2015) to $0.44 per share. Throughout all of this, the preferred shares maintained their $3 per share value.

What happened? Due to a number of circumstances, including the company’s failure to meet its financial forecasts, things started to get hairy last year. By June 2015, the board forecast it would run out of cash in 30 to 60 days, which led to the BlackBerry sale.

Needless to say, common shareholders haven’t taken the news well. Good Technology and its directors are being sued in Delaware for breaching their fiduciary duties by allowing the company to be sold for too low of a price – one that allowed the preferred shareholders to enjoy their liquidation preferences to the detriment of the best interests of the common stockholders.

That’s not the only suit: one day prior to the BlackBerry deal closing, Good Technology itself sued the former CEO of Good and some venture capital investors who wanted to block the deal. The suit alleges that the former CEO and other shareholders breached a 2013 voting agreement by failing to sign written consents in favor of the deal and attempting to exercise their appraisal rights.

Unusual circumstances? Actually, not at all. Liquidation preferences and voting agreements are pre-negotiated, completely common arrangements in the world of venture capital. It remains to be seen, however, how the court will react to these suits.

Is Your Recapitalization or Sale Entirely Fair?

Situations like this call to mind the 2013 Trados decision – a landmark decision that gives insight into a board’s fiduciary duties when board members might “represent” a class of preferred stock.

In Trados, we learned that directors are accountable first and foremost to common shareholders (and not to preferred shareholders) when it comes to exercising their fiduciary duties.

Moreover, during the sale of a company, directors must exercise their Revlon duties, which are to create and follow a process that is designed to obtain the best price for stockholders during that sale.

Where there are no unconflicted, independent directors able to run a sales process, and shareholders later sue, courts will not give the board any deference. Instead, courts will apply the very difficult “entire fairness” standard of review. In Trados, the court determined the price was fair but the process was not.

Trados isn’t a singularity. In Nine Systems Corp., a down round recapitalization case, a Delaware court found that directors breached their fiduciary duty when the recapitalization of the company was achieved through an unfair process, even though the price was fair. This is a particularly tough result for the directors given that, at the time of the recapitalization, the company’s prospects were extremely dim. As this memorandum by Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati notes, the four year path from barely remaining a going concern to the ultimate sale of the company years later was fraught.

According to this memo by Morris Nichols Corporate Counseling Group, the court found the breach of duty was evidenced by factors such as “the failure to hire an independent financial advisor, the board’s ignorance of how the $4 million valuation was derived, and the board’s failure to obtain input from the one independent director.”

If history repeats itself in the Delaware courts – and it’s likely, since Delaware courts are usually wildly consistent in their approach to similar issues – Good Technology and its directors will not be viewed favorably if they failed to implement an appropriate process when they decided to sell the company.

Independent Directors: Empanel Them Sooner than Later

If all you have on your board are directors who represent various series of preferred stock and your company hits a rough patch requiring a quick sale, your board will be vulnerable. You may be sued by unhappy holders of common stock, and the court will not give your recapitalization or sales process any deference. Instead, you risk going to trial under the entire fairness standard of review.

Tough times, however, are not the best time to start empaneling independent directors. Instead, consider empaneling a few independent directors who are not aligned with any particular investors while things are still going well.

Clearly when a company is considering empaneling independent directors it will, first and foremost, want to empanel directors who will be strategically insightful and helpful to the company. An additional consideration in light of Trados and Nine Systems, however, is making sure you have directors that everyone else with conflicts can rely on to run a good process if the company’s valuation goes south.

Any sophisticated director can reasonably predict that there may be some circumstances where he or she could be accused of a conflict of interest – as in the sale of a company if that director represents preferred shares.

This chance of being sued, of course, goes up when there is financial stress for a company, including bankruptcy.

In my article on the Trados case (linked to previously), I outlined the need to have independent directors during the sale of a company:

Consider forming a special committee—comprised solely of independent directors—to oversee the sale of a company. When selling a company, consider conflicts from a “what is the worst possible interpretation of what we are doing” perspective. This might mean appointing new directors who do not represent venture funds (and are not too friendly to the represented venture funds either, for that matter). The Trados court afforded the Trados board no deference because a majority of the board had conflicts of interest. As a result, the board could not win a motion to dismiss and instead endured a trial under the difficult “entire fairness” standard of review.

In the end, all directors are charged with maximizing returns for the common shareholders. Doing this well includes avoiding needless litigation by forming an independent committee to run a process that, if challenged, the Delaware courts can respect.

The views expressed in this blog are solely those of the author. This blog should not be taken as insurance or legal advice for your particular situation. Questions? Comments? Concerns? Email: phuskins@woodruffsawyer.com.

Author

Table of Contents