Blog

Duty of Oversight Claims: Hard to Prove but Boards Need to Be Proactive

In the past several years, board oversight claims, also commonly referred to as Caremark claims, seem to have taken a concerning turn for directors as we’ve seen a series of these cases survive a motion to dismiss.

Marchand v. Barnhill (“Bluebell ice cream” case) is one notable Caremark lawsuit in recent years, as is Clovis Oncology, Inc. Derivative Litigation. This string of cases is concerning because monetary settlements of oversight cases would typically not be indemnifiable by the company, something that puts a lot of pressure on having “Side A” D&O insurance. (As a reminder, Side A D&O insurance provides first dollar coverage for claims that are insurable but not indemnifiable)

Having said that, directors should be heartened by the fact that it is not easy for plaintiffs to survive a motion to dismiss if their claim is a frivolous one. A Delaware court demonstrated this recently in the MoneyGram International case, Richardson v. Clark.

A Director’s Duty of Loyalty: Brief Background

The duty of corporate oversight is part of a director's fiduciary duty of loyalty to monitor a company’s operations. Shareholders sue directors for allegedly failing to make a good faith effort to execute these oversight duties.

To establish an oversight claim under Delaware law, the plaintiff must prove that either:

- Directors had utterly failed to implement any reporting or information system or controls, or

- Having implemented a system or controls, consciously failed to monitor or oversee operations thus disabling themselves from being informed of risks or problems requiring their attention.

The 2019 Delaware Supreme Court Marchand decision focuses on the first type of Caremark case (the first bullet above): The failure of a board to implement a monitoring system that ultimately resulted in three consumer deaths. I have written about this case in an earlier article on the importance of board-level monitoring.

In another Delaware case in 2020, the Clovis decision centered on the second type of oversight claim: The failure of directors to heed the red flags waved in front of them. In this case, the Clovis board failed to appropriately monitor the clinical trials and as a result, allegedly allowed the company to release misleading statements about the drug. I wrote about this case in an earlier article on board oversight.

Oversight claims can yield massive financial settlements for plaintiffs, as illustrated in the Pacific Gas and Electric Company derivative lawsuit that paid out $90 million for directors failing to maintain the safety of a pipeline that resulted in eight deaths. I wrote more about this in an earlier article on the five types of derivative lawsuits with massive settlements.

In all cases, oversight claims underscore the importance of the role that the board plays when it comes to corporate risk oversight, and provides useful lessons for avoiding this type of claim.

While the lawsuits mentioned above survived their motions to dismiss, that is certainly not always the case. Notwithstanding some of these recent cases, Caremark oversight cases are typically very hard for plaintiffs to prove, as demonstrated by in Richardson v. Clark (the MoneyGram case).

The MoneyGram Derivative Suit

MoneyGram International, Inc. facilitates the transfer of money among businesses and individuals worldwide. However, bad actors can and have used it for money laundering and fraud.

The government, of course, wants MoneyGram to stop its system from being used for nefarious purposes. In 2012, dissatisfied with MoneyGram’s efforts, federal prosecutors stated that MoneyGram failed to comply with anti-money-laundering requirements and that the company aided and abetted wire fraud.

To avoid prosecution, MoneyGram entered into a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) that required a large payment for restitution to injured customers as well as the promise to take certain actions to prevent future wire fraud and money laundering over the next five years.

MoneyGram made efforts to comply with the actions that DPA imposed over the next several years, but those efforts were considered insufficient given that complaints of fraud and illegal activity did not diminish. In 2017, regulators threatened MoneyGram with prosecution on the original charges. To avoid prosecution, MoneyGram agreed to extend the DPA through 2021 and pay an additional $125 million in restitution.

In the derivative suit Richardson v. Clark, the plaintiff alleged that the board and two officers failed to ensure that MoneyGram fully complied with the requirements of the DPA. In addition, the claim alleged that the deficiencies in the software MoneyGram used to reduce fraud, once discovered, were not fully disclosed to regulators.

These actions, the plaintiffs argued, were enough to establish that directors acted in bad faith as it relates to oversight duties.

Defendants filed a motion to dismiss on the grounds that the plaintiff did not follow Delaware Court of Chancery Rule 23.1 to first make a demand on the board. The gist of this rule is that shareholders who allege wrongdoings that are harming or have harmed a corporation must first ask the board to look into the matter before bringing a lawsuit.

A derivative lawsuit of the type brought by the plaintiffs in the MoneyGram case is only proper if the board is too conflicted to be able to make an independent judgment about whether to pursue litigation against an individual or group of individual directors and officers.

Plaintiffs can bypass the step of first approaching the board for redress if plaintiffs can prove the demand would be futile because the board of directors lack independence (director independence was a key fact in the Marchand case), or something else that would cause them not to act in the best interest of the company.

In the case of MoneyGram, the plaintiff claimed that demand was futile because “the company’s directors face liability in this action, inhibiting their ability to act in the interest of MoneyGram.”

In December 2020, the Delaware Court of Chancery granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss. The court found that the plaintiff failed to plead the type of particularized bad faith facts that would excuse demand.

The Decision

Plaintiffs attempted to excuse their failure to first make a demand on the board by alleging that the demand was futile. The plaintiffs asserted that since all the directors were defendants, the directors had an interest in the outcome of the case.

The court rejected this contention as it has in the past, noting that the plaintiff’s logic was circular: There is no point in having Rule 23.1 if the mere fact of being named as a defendant erases a board’s independence.

The court found that the plaintiff did not prove demand was futile. To prove demand futility, the court requires “‘particularized factual allegations’ creating a ‘reasonable doubt that, as of the time the complaint is filed, the board of directors could have properly exercised its independent and disinterested business judgment in responding to a demand.’”

In its analysis, the court found that:

The Plaintiff does not challenge the independence of a majority of the Board. Instead, the Plaintiff alleges that a majority of the Demand Board is interested in the outcome of the litigation, because they face “a substantial likelihood of liability” for the claims asserted in the Complaint. Mere “potential directorial liability is insufficient to excuse demand.” The fact that wrongdoing is alleged against the directors themselves or that directors are named defendants in an action does not by itself deprive them of independence; otherwise, compliance with Rule 23.1 in derivative pleadings would be self-proving. Instead, a plaintiff must plead facts implying a substantial likelihood of directorial liability to satisfy the rule.

To the contrary, the court’s opinion outlined the steps that MoneyGram took to comply with the DPA, including establishing a compliance committee to fight fraud.

The plaintiff acknowledged in oral arguments that MoneyGram took the actions required by the DPA to reduce fraud, but argued that the company’s ad-hoc efforts were insufficient. The court’s opinion stated that “this allegation simply tells me the Board did a poor job applying its discretion to act; to my mind, this does not reasonably imply bad faith.”

Another allegation intended to establish bad faith on behalf of the directors was that the original software implemented to fight fraud was insufficient and resulted in an increase in fraud complaints.

To this, the court replied: “The mere implementation of an unsuccessful program cannot support liability for lack of oversight, however. Perhaps most obviously, implementing a particular fraud reduction software demonstrates attention to risk, rather than disregard of it. It is not reasonably conceivable under the facts pled that MoneyGram’s choice to implement Actimize was made in bad faith. There are also no allegations that MoneyGram didn’t try to fix the problems with Actimize.”

The plaintiff went on to argue that MoneyGram concealed the software’s deficiencies from the US Department of Justice. To that, the court stated that it understood their argument to establish bad faith, but that it disagreed:

A finding by the DOJ of inadequate disclosure, after the company had replaced the Actimize software, and without more, fails to amount to a particularized allegation that the Director Defendants, with scienter, misrepresented problems with Actimize to the DOJ. No particularized facts pled with respect to MoneyGram’s use of Actimize implicate bad faith on the part of the Director Defendants.

All in all, the court did not believe the plaintiffs had alleged sufficiently particularized facts that the directors acted in bad faith, which is required to survive a motion to dismiss under a Caremark case:

Board along with its Directors’ alleged failures to act, individually and together, I cannot conclude that a majority of the directors acted in bad faith. A conscious failure to act in the face of a known duty can amount to bad faith. Here, the Complaint describes directors who oversaw a company struggling to implement long-term reforms; a Board that kept itself apprised of progress, or lack thereof, and which failed to take remedial or punitive efforts against management failures. The Director Defendants on the alleged facts may be plausibly accused of feckless oversight and lack of vigor; they may have been wistless or overly reliant on management. These facts, I find, do not implicate bad faith, however. Bad oversight is not bad-faith oversight, and bad oversight is the most that these facts could plausibly imply.

Lessons Learned

MoneyGram is a good example of something I often say to boards: The law doesn’t demand that you get things right, only that you tried. This is why the MoneyGram board won its motion to dismiss notwithstanding having just agreed to another DPA and a large fine.

That said, it remains the case that boards are well served to implement and oversee the proper risk mitigation systems.

Some useful steps for board directors as they are contemplating their oversight duties:

- Identify the most critical risks facing your company and establish a monitoring system that brings information to the board about these risks in a timely way.

- Once the oversight system is established, pay attention and take corrective actions as needed.

- Document everything. These types of cases are generally preceded by a Section 220 Books and Records request to examine the minutes of the board. If this happens, you will want to deliver to the plaintiffs a mountain of documents that demonstrate how thoroughly the board exercised its duty of oversight. I’ve written in the past about the importance of good board meeting minutes, as well as the importance of following good note-taking hygiene practices for corporate directors.

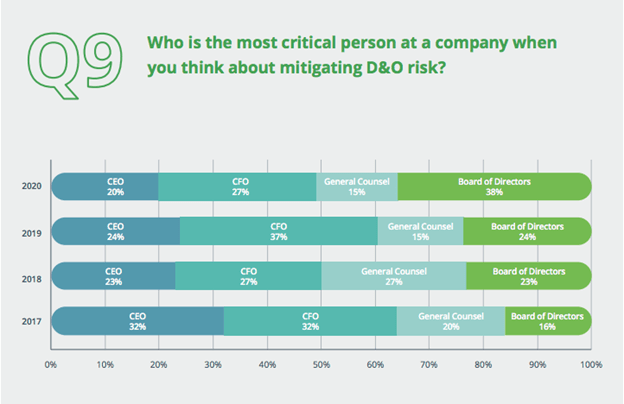

On a final note: D&O insurers increasingly care about the quality of the board of the public company they will insure. In the eighth-annual edition of the D&O Looking Ahead Guide, we asked underwriters: Who is the most critical person in a company when you think about mitigating D&O risk?

In 2019, 24% of insurance underwriters stated the board of directors. In 2020, that number jumped to 38%.

In 2019, the CFO was considered the most critical person to mitigating risk. In 2020, however, insurers are looking to the board to mitigate D&O risk. This is likely due, at least in part, to a jump in derivative suits against directors and officers that have paid out large settlements.

Companies with good boards will want to emphasize the board’s involvement in risk mitigation as they go through the D&O insurance process.

Author

Table of Contents