Blog

Slack Goes to Washington: Direct Listings, Section 11 Suits, and the Supreme Court

The D&O liability landscape is poised to change—or not—depending on how the US Supreme Court rules in the long-running Section 11 case against Slack.

The Supreme Court heard oral arguments in this case on April 17, 2023, and is expected to issue a ruling this summer. This article discusses the Slack case and provides some guidance for directors and officers.

Background: Direct Listings 101 and Rates of Litigation

Slack (now owned by Salesforce) went public on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) through a direct listing back in 2019. This was a fairly new method of going public at the time, with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) having only approved the NYSE’s rules for direct listings in 2018.

Going public through a direct listing is an innovation intended to address those private companies that are ready to go public but do not need to raise capital for themselves, and want to provide liquidity to their shareholders—particularly their employees and their long-term investors that are ready for liquidity.

These companies do not necessarily want to raise the additional capital—and pay the expensive investment banker fees—that comes with doing an IPO.

Direct listings also typically do not have a period in which the pre-public shareholders are restricted from selling their shares (a “lock-up period”).

In addition, some investors have been concerned that the structure of the IPO process can cause investment banks to underprice the IPO, further diluting current shareholders. Since no new shares are issued in a direct listing, current shareholders are not diluted.

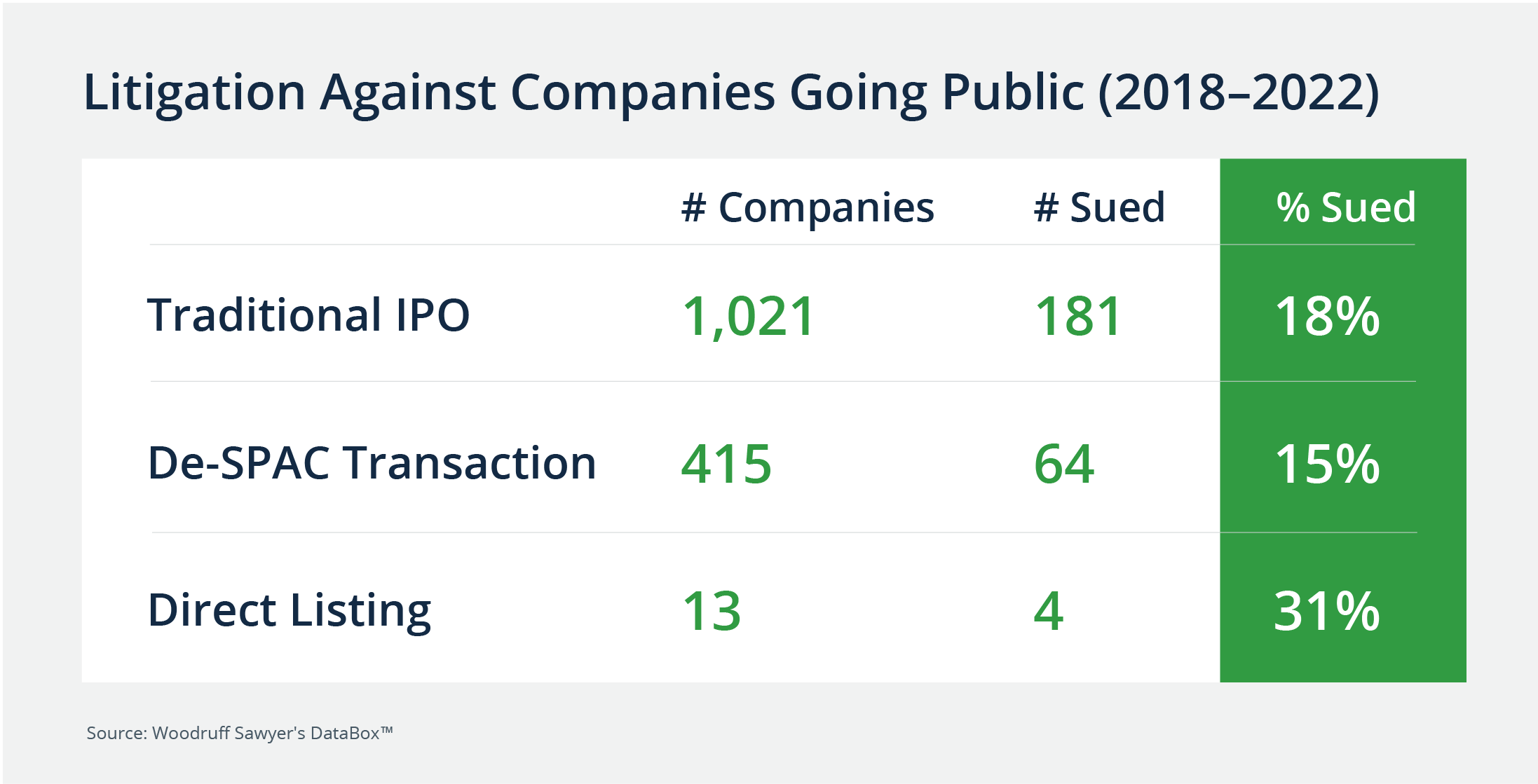

As compelling as these reasons may be, traditional IPOs and even de-SPAC transactions are far more popular paths to going public than direct listings. From 2018 through 2022, there have been only 13 direct listings:

In the same five-year period (2018–2022), there have been 1,021 IPOs and 415 de-SPAC transactions.

Are litigation rates against direct listings better than litigation rates against new public companies? No—but the small number of direct listings compared to other ways to go public makes this a difficult comparison.

From 2018 through 2022, 18% of the 1,021 companies that went public through a traditional IPO had a securities class lawsuit filed against them.

In the same five-year period, 15% of the 415 companies that went public through a de-SPAC transaction had a securities class action lawsuit filed against them. This compares to 31% of direct listings with a class action—which is to say four of 13—in that same period.

For context, remember that in each of the years in the five-year period ranging from 2018 through 2022, the percent of all public companies that were sued ranged from 3% to a high of 5%.

In other words, new public companies, however they chose to go public, are sued a lot more frequently than everyone else.

Slack Shareholders Bring Suit

Companies that go public through a direct listing have an initial reference price instead of an IPO price.

Like with a traditional IPO, companies engaging in a direct listing also register shares through an S-1 registration statement (F-1 for foreign filers)—but shares can enter the public markets not pursuant to the registration statement as well.

As I discussed in an earlier article, in the case of Slack’s direct listing, while Slack registered approximately 118 million shares, an additional 165 million additional shares were available for resale into the public market at the time of the direct listing.

When a company doing a traditional IPO sees its stock price fall below the initial offering price, the company knows it is likely to be sued by plaintiffs pursuant to Section 11 of the Securities Act of 1933.

The "Tracing" Requirement

Plaintiffs that can trace their purchase to the company’s registration statement will allege that there were material misstatements and/or omissions in the registration statement.

Plaintiffs like Section 11 cases because the company basically has strict liability for material misstatements and omissions.

This contrasts with Section 10b cases under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. To win these cases, plaintiffs have to show that the defendants made misstatements knowingly (or at least very recklessly) to prevail in those cases.

Note that the tracing requirement, based on the language of the statute, is one that has been accepted by courts for a long time.

It has also been a relatively easy requirement for plaintiffs suing companies that just did a traditional IPO since, traditionally, only shares sold pursuant to the S-1 registration statement were traded in the public market for the first six months of a public company’s life. This is because, as part of the IPO process, existing shareholders would agree to sign a lock-up agreement prohibiting them from selling their shares until six months after the IPO.

Even after the expiry of the lock-up, tracing was reasonably easy given the relatively slow rate at which shares not issued pursuant to a registration statement typically flow into the market.

Turning back to direct listings, one can immediately see the problem with Section 11’s tracing requirement. When a company goes public through a direct listing, buyers will not know whether or not the shares they purchased could be traced back to the company’s registration statement. Indeed, in Slack’s case, more shares were in the market from sources other than the registration statement than pursuant to the registration statement, as noted above.

Slack's Argument About the Tracing Requirement

When plaintiffs sued Slack after its shares fell below its reference price, Slack argued first in federal district court and later in front of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals that plaintiffs lacked standing to bring suit under Section 11 because the plaintiffs could not meet the tracing requirement.

The Ninth Circuit disagreed, expressing the concern that to do otherwise would render direct listings utterly free from the specter of Section 11 liability.

What Will the Supreme Court Decide?

There are a lot of technical legal arguments being made by a lot of very smart people on both sides of the Slack case. In the end, however, there are two conflicting “policies” that the Supreme Court will have to resolve.

On the one hand, it seems very strange that a company could get out of the Section 11 liability that everyone knows comes with a registration statement merely by choosing to go public through a direct listing instead of a traditional IPO.

Members of the SEC usually take the position that Section 11 liability is a feature, not a bug.

The idea is that Section 11 creates the right incentives for the company going public and its various advisors to engage thoughtfully and thoroughly when it comes to the diligence that supports statements made to the public about the proposed public company.

Indeed, we have seen exactly this argument made when members of the SEC have expressed concern about the perception of lower liability associated with de-SPAC transactions compared to traditional IPOs. This is certainly the animating impulse behind the proposed rules the SEC has issued for SPACs and de-SPAC transactions.

On the other hand, there is a long history of requiring tracing for standing to bring Section 11 claims based on the text of the statute. It arguably falls to Congress, not the courts, to change this rule if Congress thinks it should be changed.

Having said that, it is not just a question of policy. The tricky technical legal issues at play are real, as noted in this excellent article by Joseph Gross of the Wiley firm.

The article notes, for example, that while plaintiffs generally bring suits under both Section 11 and Section 12(a)(2) of the ’33 Act, there are differences between the two that may end up being relevant in the Slack case.

What Does This All Mean for Directors and Officers?

First and foremost, regardless of the outcome in the Slack case, companies preparing to go public—through whatever modality including a direct listing or a de-SPAC transaction—should be prepared to engage in an exhaustive due diligence effort.

Remember that even if it turns out Section 11 does not apply to a particular offering, plaintiffs and the SEC have plenty of other ways to pursue directors and officers of companies that put out sloppy disclosure.

If Slack prevails and plaintiffs are found not to have standing to bring Section 11 claims, we should expect some effort to have Congress modify the language of Section 11 to apply it to direct listings.

If this gets traction—which feels unlikely given all of the other matters currently before a distracted US Congress—expect to also see modifications to securities laws to address de-SPAC transactions.

As always, D&O insurance will remain an important item on the checklist for companies contemplating going public.

| Learn more in Woodruff Sawyer’s Guide to D&O Insurance for IPOs and Direct Listings. |

D&O insurance carriers have, to date, treated direct listings much like traditional IPOs. This is to say that the price of D&O insurance whether going public through a direct listing or a traditional IPO has been the same.

If Slack prevails, however, there will be an argument that direct listings should be able to pay less for D&O insurance than IPO companies since they do not have to worry about Section 11 liability.

On the other hand, if Slack loses, the consequences could go further than just direct listings.

Recall that mature public companies do follow-on offerings of their securities. These issuances are done pursuant to a registration statement and thus implicate Section 11 liability.

Section 11 liability may also be an issue when public companies use their securities as currency for M&A transactions.

As it stands now, the longer a company has been public, the more difficult tracing for a follow-on transaction—and even an M&A transaction—may be since the market is awash with other shares of the issuer.

From a liability perspective, this has been helpful for mature public companies engaging in these transactions. But if the Supreme Court issues a losing decision for Slack that loosens up previously tight requirements, all bets may be off.

Author

Table of Contents