Blog

Are You Overpaying for Your D&O Insurance?

No one wants to overpay for their insurance. Playing on this concern, one of the cheekier sales tactics some brokers use is to show a prospective client a chart that compares the price per million Company A is paying for its D&O insurance with what Company B is paying. If Company A’s price per million is more than that of Company B, is Company A paying too much?

I characterize the move as cheeky because it’s a tactic that is typically only used when the person showing the chart has no plans to offer a clear explanation about how pricing for D&O insurance really works.

The rest of this post offers some information about how D&O insurance is priced, including an explanation of two common pricing “ploys” that can be misleading if you don’t fully understand their dynamics.

The Price per Million Ploy

First and foremost, the problem with the chart I described above is that it ignores the fact that when you buy more insurance, the price per million usually declines. Remember that D&O insurance programs are typically put together in horizontal layers. One carrier may write the first $10 million of limit. Another carrier will take the next $10 million of limit, and so on. This goes on until you have the total program you want, be it $20 million to $200 million or more in total insurance limits.

Unsurprisingly, the price per million for each higher layer of insurance you purchase is usually less than the price of the underlying layers. This makes sense: in any given claim situation, the chance that a higher layer of insurance will ever actually be accessed is less than the chance for the lower layers.

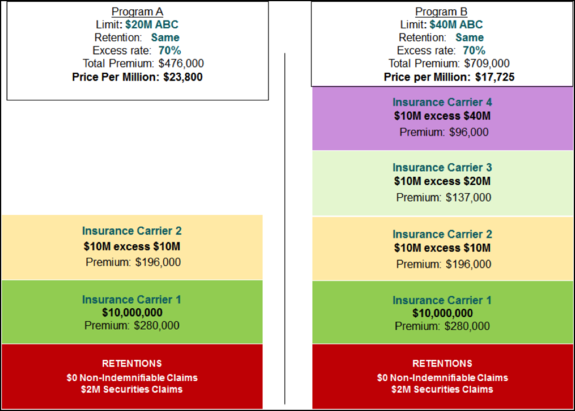

Here’s an example to illustrate my point about how using price per million as a metric can be problematic: Imagine that you are comparing two D&O insurance programs, one for $20 million in insurance limits, and the second for $40 million. For the purposes of my example, assume that the self-insured retention is the same for both. Also assume that the policy terms and carrier quality are consistent between two programs.

Here’s the pricing for the two programs, broken down by each layer of insurance:

Program A, the smaller $20 million program, costs $23,800 per million. That’s certainly more than $17,725 per million that the buyers of Program B are paying.

But are the Program A buyers overpaying? Of course not. This is all just math. And if the Program B buyers don’t need to buy $40 million in limits, the “more expensive” price-per-million program, Program A, actually represents a 33 percent savings compared to Program B. Purchasing the appropriate amount of limits yields a saving of about $233,000.

The Premium Decrease versus Rate Decrease Ploy

Do you want a premium decrease or a rate decrease? Clearly you’d like both, but when your total premium cost goes down in some cases, your premium decrease is, in fact, also a rate increase.

A premium decrease just means you are paying less in premiums compared to the prior year. However, premium decrease might not actually mean that your insurance is on sale.

The easy example is when a company purchases less in overall insurance limits compared to the previous year. The premium for the program will decrease because you have bought lower limits, but the trade-off is the company's retaining more risk.

A trickier example is when your premium decreases because your self-insured retention (“SIR,” similar to a deductible) goes up. Your premium decreased, but your rate did not.

Any carrier will charge you less for your insurance if you increase your deductible from, say, $1 million to $2 million or more. You might be willing to trade increased exposure for a lower premium—just be sure you understand that this is, in fact, the trade you are making.

Finally, remember that you are getting a premium decrease but a rate increase any time a carrier narrows the scope of coverage of the insurance program.

Market Forces

While there are some things you can control when it comes to your D&O insurance rates (like starting the renewal process early and buying the right amount of insurance), there are market forces that impact pricing as well.

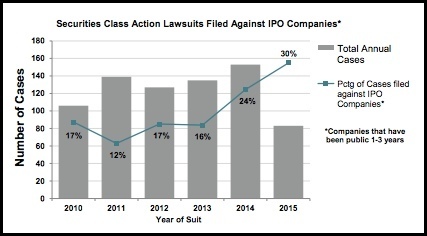

Take, for example, the rise in lawsuits against IPO companies within the first three years of going public:

Source: Woodruff Sawyer’s DataBox Mid-Year Securities Class Action Report

Any individual IPO company may not be sued within three years of going public, but each IPO company will experience higher pricing as a result versus if this unfortunate IPO litigation trend were not taking place. Carrier appetites change in the face of things like litigation trends. This means charging more for D&O insurance or perhaps declining to provide a quote for particular types of companies altogether.

There are also other market dynamics that can impact a company’s D&O insurance pricing, such as capital availability, investment returns on premiums and even industry consolidation.

D&O Insurance Is Not a Commodity

Finally, when it comes to D&O insurance, pricing should never be the end of the analysis. D&O insurance is a highly customized financial instrument. The policy contracts are not standardized. Rather, the same carrier has the discretion to (and will) offer many different versions of various terms to different insureds depending on a variety of factors.

Put differently, money spent on an insurance program with broad coverage terms offered by a quality insurance carrier is always going to be a better value for your company than a less expensive program with poor contractual terms offered by a carrier who really has no intention of paying any future claims.

Pricing is of critical importance, but your savings were illusory if obtaining a lower price meant living with an inferior insurance contract written by a less-than-excellent insurance carrier.

The views expressed in this blog are solely those of the author. This blog should not be taken as insurance or legal advice for your particular situation. Questions? Comments? Concerns? Email: phuskins@woodruffsawyer.com.

Author

Table of Contents