Blog

Direct Listings vs. IPOs: Liability and Litigation, Part 2

Direct listings are the unconventional cousin to traditional IPOs. Three companies have successfully completed a direct listing in recent years, and Nasdaq and NYSE are hoping for more. You can read more about the differences between direct listings and IPOs in an article I posted last week.

Given that direct listing is a newer process, the litigation risks are less known, but we do have some data.

We know that litigation levels are elevated for newly public companies in their first three years of being public. We're also aware that Section 11 securities class actions that allege material misstatements and omissions are widespread.

It may be the case, however, that direct listing companies may fare better than traditional IPO companies when it comes to post-listing litigation.

Direct Listings Litigation

One out of the three companies that followed the direct listing path has been sued thus far: Slack.

Slack completed its listing in the summer of 2019. By fall it was sued in both state and federal courts for claims under Section 11 of the Securities Act of 1933. The plaintiffs claim that Slack's S-1 registration statement was false and misleading. Update: Click here for the latest on the Slack litigation.

Readers of my blog know that Section 11 claims in state courts are a troubling trend right now, especially for newly public companies.

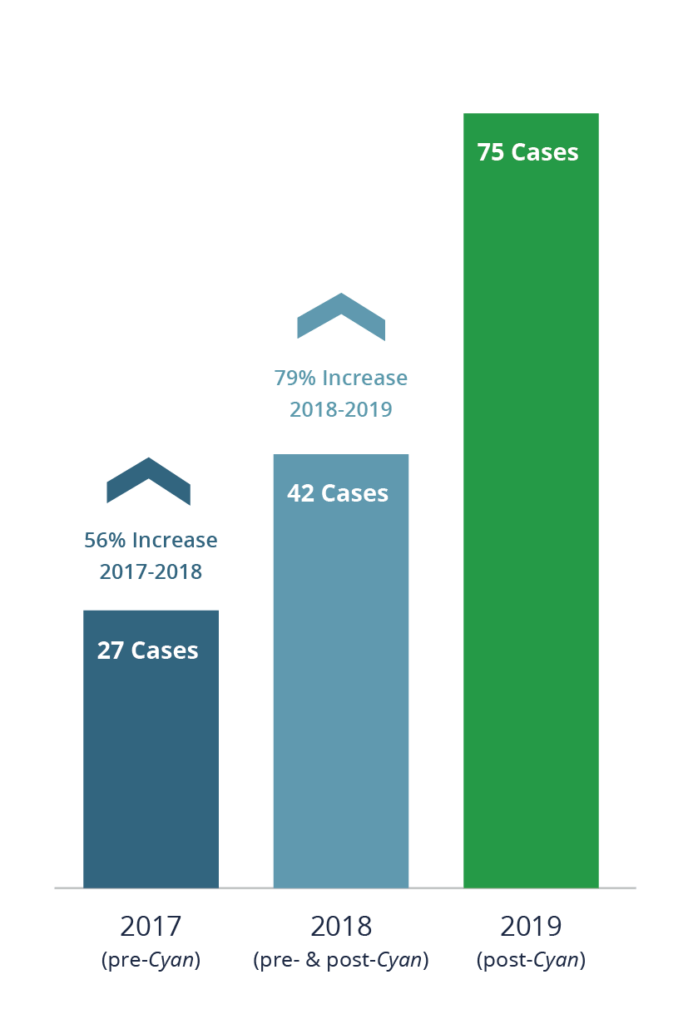

[caption id="attachment_22713" align="alignnone" width="693"] The impact of Cyan: Section 11 cases increased by 79% from 2018 to 2019.[/caption]

The impact of Cyan: Section 11 cases increased by 79% from 2018 to 2019.[/caption]

But Section 11 cases for direct listing companies may see better outcomes.

Consider the fact that damages in a Section 11 case rely on each plaintiff being able to trace the shares purchased back to the registration statement.

This is easier for an IPO, particularly within the first 180 days, because the only shares in the market were sold pursuant to the registration statement. This is a consequence of the 180-day lock-up imposed by the investment bankers for all IPOs. (See last week's article for more.)

However, in a direct listing situation, this tracing is much more difficult. As I've written about in the past on follow-on offerings and litigation:

If plaintiffs cannot meet the tracing requirement, they do not have standing to sue under Section 11. Without standing, plaintiffs are not able to sue for material misstatements and omissions in the registration statement pursuant to Section 11.

Tracing can be a rigorous, difficult requirement—but not shortly after an IPO. Immediately after an IPO, the only shares in the float (being traded in the market) are the shares that were shares registered by the IPO's S-1 registration statement.

This usually remains true until the expiration of the lock-up on all shares that existed before the IPO. (A "lock-up" refers to the near-universal practice of investment bankers requiring that existing shareholders agree to continue to hold their shares for six-months after an IPO.)

Indeed, this is very much the argument Slack is using in its defense for the Section 11 suit that has been filed against it. Slack has argued to the court that direct listings make tracing to the S-1 registration statement impossible, and for that reason the plaintiff's Section 11 suit must be dismissed.

In addition, Slack is arguing that even if plaintiffs could overcome the tracing problem, plaintiffs have no way to seek damages since there was no offering price, only a reference price.

Of course, we do not yet know if all state and federal courts will agree with Slack's arguments and grant Slack's motion to dismiss. If the answer is no, the courts do not agree with Slack's reasoning, direct listings are no worse off than traditional IPOs when it comes to litigation.

The more likely situation is that the lack of traceability may discourage plaintiffs from bringing claims.

After all, if damages are either greatly reduced or not available at all, the plaintiffs' firms will not get a big payout in the end. This makes bringing a case in the first place a losing proposition for plaintiffs.

D&O Insurance for Your Direct Listing

When it comes to D&O insurance for a direct listing, the process is very similar to the one we follow for an IPO.

The biggest differences have to do with taking the time to ensure that your D&O insurance underwriters understand the direct listing process.

Insurance underwriters are as interested in the prospects for direct listings as anyone else and are keeping a careful eye on the situation.

To that end Woodruff Sawyer hosted a presentation and Q&A session attended by some of the major D&O insurance carriers towards the end of 2019 in order to give the community more information about this novel path to going public.

In terms of D&O insurance limits, at this time we do not have enough data to suggest that direct listing clients should purchase less in limits than they otherwise would have. Moreover, there are other reasons not to reduce limits.

The D&O insurance purchased at the time of an IPO or direct listing is not just for the going-public exposure; the D&O policy is also there to respond to other exposures that have not changed. An easy example is the Section 10(b) exposure companies face for disclosures in their 10-Ks and 10-Qs.

It is well known at this point that the pricing for D&O insurance for IPO companies is extremely high. This is as a result of the litigation environment of the past several years, which has included a surge in Section 11 claims in state court.

The good news is that this situation should start to resolve in light of a recent Delaware Supreme Court decision in Sciabacucchi v. Salzberg. Of course, it will take time for the results of this case to work through the system.

Carriers may feel that they do not yet have enough data to determine if direct listings will be sued more or less frequently than IPOs. Based on what we know about the process and the law, however, direct listings are certainly not riskier than their IPO counterparts.

Thus, the price of D&O insurance for a company doing a direct listing should not be more than if the company were to do an IPO. Indeed, based on the tracing issues, one hopes that some carriers decide to price D&O insurance for direct listings in a favorable manner.

If this is the case, pricing will be yet another reason for companies to consider doing a direct listing instead of a traditional IPO.

Author

Table of Contents