Blog

Direct Listing Companies Not Immune to Section 11 Suits

Direct listings are an intriguing new way to go public. As I've discussed in an earlier post, there are some significant advantages to direct listings. Unfortunately, immunity from Section 11 suits is not one of those advantages.

Slack is one of three companies that has completed a direct listing to date. We have been following the Section 11 suits filed Slack after its stock price fell below its initial reference price. Slack is currently defending itself against a suit filed in federal court (U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California) and one filed in state court (Superior Court of California for the County of San Mateo). Based on a recent decision in the federal action, it looks like direct listing companies will not be treated differently than traditional IPO companies.

This is disappointing. Many of us had hoped that the nature of direct listings would lead to a less lucrative litigation target for the plaintiffs' bar.

A Brief Background on Section 11 Suits and Newly Public Companies

The broader context of Section 11 suits is helpful to understand why the recent opinion in Slack's litigation is significant.

Section 11 suits under the Securities Act of 1933 are one of the more common types of litigation against new public companies. In these suits, shareholder plaintiffs allege that there are false and misleading statements in a company's S-1 registration statement.

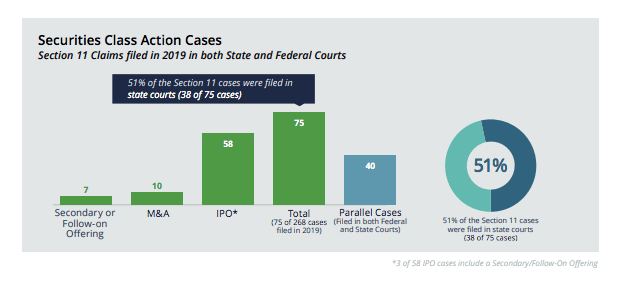

This type of litigation has steadily been on the rise, with a sharp increase in Section 11 lawsuits over the past couple of years. The increase was due to a 2018 Supreme Court decision in Cyan v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund that would allow Section 11 suits to be brought in state court even though traditionally they were a federal court matter.

Not only did we see the number of Section 11 suits rise 79% after Cyan, we also saw 40 parallel filings in 2019. A parallel filing occurs when a company faces the same set of allegations in state and federal court.

[caption id="attachment_25539" align="alignnone" width="622"] - Flash Report: 2019 Year-End Summary, D&O DATABOX, Woodruff Sawyer[/caption]

- Flash Report: 2019 Year-End Summary, D&O DATABOX, Woodruff Sawyer[/caption]

(As an aside, there are now things companies can do to help stop this type of frivolous litigation and I have outlined that here.)

Typically, plaintiffs have standing to pursue a Section 11 suit only if plaintiffs can trace shares back to the registration statement in question. This is relatively easy to do with a conventional IPO, particularly if a suit is brought soon after an IPO, since the only shares traded in the market within the first six months are typically those registered in the IPO's S-1 registration statement.

Direct listings, however, offer no primary (new) shares of the company. Instead, the company registers secondary shares (shares the company previously sold to third parties) on the registration statement. In addition, current holders of shares can also sell into the market not pursuant to the registration statement. Since registered and unregistered shares simultaneously hit the market, tracing shares back to the registration statement in a direct listing is nearly impossible.

Many hoped that fact alone would be enough to discourage plaintiffs from filing Section 11 suits against direct listing companies. Not so, as we are finding out in this first Section 11 suit involving Slack's direct listing.

Slack's Section 11 Suit: New Developments, New Lessons

In Slack's direct listing, the company filed a registration statement with approximately 118 million registered shares. An additional 165 million additional unregistered shares were also immediately available for resale.

When Slack's stock price fell below its initial reference price, one of the Section 11 suits filed against it by plaintiffs was filedin federal court. This suit names the CEO/Chairman, the CFO, the CAO, and the directors of the company.

Plaintiffs specifically noted in their complaint that they bought shares "pursuant and/or traceable to the Company's registration statement and prospectus."

In its motion to dismiss Pirani v. Slack Technologies, Inc., Slack argued that plaintiffs lacked standing to bring a Section 11 case because it would be impossible for plaintiffs to trace their shares back to the registration statement.

Slack also argued that plaintiffs could not establish damages because there was no offering price (only a reference price exists in a direct listing).

Standing to Bring Suit

The court noted that the question of traceability and direct listings is a question of first impression given that the SEC has only recently allowed direct listings to take place.

The court disagreed with Slack's contention that plaintiffs lacked standing to bring suit due to problems with traceability.

In its opinion, the court seemed sympathetic to plaintiff's concerns that, if Slack's argument were to prevail, the court would essentially be creating a roadmap for companies to avoid Section 11 liability for defective registration statements.

On this point, plaintiffs had asserted that limiting plaintiffs to the normal confines of a standard tracing analysis "would eviscerate the rights afforded by Section 11 and allow companies to eliminate Section 11 liability by releasing nonregistered shares into the market at the same time as registered shares."

From a summary of the case from the Orrick law firm:

The court acknowledged the Ninth Circuit precedent requiring plaintiffs to "trace their shares back to the relevant offering" in order to establish standing under Section 11. … [and] Judge Illston further agreed with defendants that it was impossible for the plaintiff to trace his Slack shares to the company's registration statement, given the simultaneous offering of unregistered and registered shares. …

Nonetheless, the court found that in the context of a direct listing, a requirement that plaintiffs trace their shares to a registration statement—a task that is likely impossible—would lead to a "result at variance with the policy of this remedial legislation." …

The court, "guided by the familiar canon of statutory construction that remedial legislation should be construed broadly to effectuate its purposes," held that the statutory phrase [from the text of Section 11] "any person acquiring such security" should be read to encompass not just any person acquiring securities traceable to a registration statement, but also to any person "acquiring a security of the same nature as that issued pursuant to the registration statement."

Clearly, the court wished to take a broader view of traceability than a strict reading might engender in order to preserve the enforceability of Section 11 liability.

Lack of Damages

The court was also unsympathetic to Slack's efforts to quash the litigation for a lack of damages as a matter of law.

Recall that damages in a Section 11 claim are calculated as the difference between a security's offering price and the price that would have been paid if all the relevant facts about the security were known.

Slack's argument that the plaintiff's case should be dismissed for a lack of damages was premised on the text of Section 11, which refers to the price a "security was offered to the public." Unlike a traditional IPO, the first price of a direct listing is a reference price established by the exchange, not a price established by the company (usually with help from the company's bankers). Since there was no offering price, the theory goes, there can be no Section 11 damages.

In rejecting this argument, the court first noted that while a lack of damages might well be an affirmative defense, damages are not an element of a Section 11 claim. As a result, it would be Slack's burden to show at the pleading stage that the plaintiff could not recover damages as a matter of law.

This is a difficult burden to meet, and the court found that Slack had not met it, almost seeming to snicker at Slack's attempt to point to its having written "not applicable" in the box on the front of the registration statement that calls for an issuer to list its "proposed maximum offering price per share." The court also mentioned plaintiff's ability to pursue a "value-based" theory of damages, which is a fact-intensive inquiry that cannot be resolved in a motion to dismiss.

Slack's litigation is just one case in one court. Still, it is instructive. At least in Slack's case, a direct listing does not enjoy immunity from a Section 11 suit merely because the shares cannot be traced and the process uses a reference price instead of an initial offering price.

Given the interest many companies have in pursuing a direct listing, we will be keeping a close eye on this case as it unfolds.

Author

Table of Contents