Blog

IPO Companies, Section 11 Suits and California State Court

This article was co-authored by Donna Moser and Vysali Soundararajan.

In 2009, a group of shareholders filed suit in federal court against CardioNet, a company that had recently completed its IPO. The shareholders sued pursuant to Section 10(b) of the Securities Act of 1934. The federal court dismissed the case. However, in 2010, another group of shareholders filed suit in California state court against the same company under Section 11 of the Securities Act of 1933. Within two years, that case settled for more than $7 million.

While the suits involved different class periods and slightly different allegations, those differences do not fully explain the results. As it turned out, CardioNet was the beginning of a new trend: plaintiffs filing Section 11 suits against IPO companies in California state court.

Fast forward to 2015, a year in which shareholders filed at least 14 Section 11 suits in California state court against IPO companies. This is a dramatic uptick in frequency relative to the preceding six years in which plaintiffs filed – in total – 15 suits ( a mere 2.5 cases per year on average). Through the first quarter of 2016, plaintiffs have already filed at least six such cases.

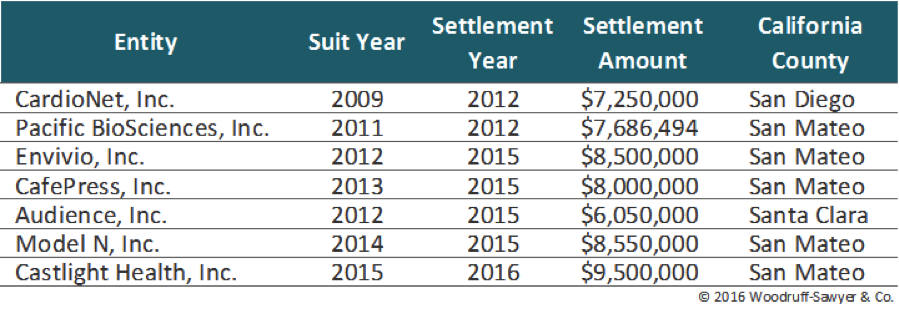

Based on the data, these cases seem especially tough for defendants. With non-existent dismissal rates and costly early-stage discovery, defendants are under significant pressure to settle. The last seven publicly disclosed Section 11 state court settlements against IPO companies have been between $6 and $10 million dollars.

How did this happen? Let’s back up for a bit of context …

IPOs are excellent when it comes to injecting capital into companies and increasing a company’s public profile. With these benefits, however, come risks. One well-known phenomenon is that companies are much more likely to be sued in the first three years following an IPO, a trend we’ve been tracking at Woodruff Sawyer for some time.

A number of factors contribute to this trend—including plaintiffs that are suddenly laser focused on suing IPO companies under Section 11 of the ’33 Act.

Section 11 claims are challenging for defendants because companies are strictly liable for material misstatements and omissions in their S-1 registration statements. The directors and officers who sign the registration statement are also subject to liability. Unlike Section 10(b) claims of the ’34 Act, plaintiffs do not have to show intent in Section 11 claims, making them easier for plaintiffs to win.

Section 11 damages are calculated as the difference between the stock price at the time of the offering (time of the IPO) and when the plaintiff shareholder sells or when the case was filed.

The relevant statute of limitations for Section 11 cases? Three years from the date of the offering.

Section 11 Cases Surge in California State Courts

The plaintiffs’ bar is nothing if not innovative, and its current focus of innovation seems to be Section 11 claims brought in California state courts. As of April 15, 2016, according to our research at Woodruff Sawyer, there are 22 Section 11 cases against IPO companies active in various California state courts. Eight of these 22 active cases also have separate ‘34 Act suits pending in federal courts.

There was a time when it was common to see federal securities class action law suits brought in state court. A series of reform acts, however, changed this dramatically. The law is clear, for example, that ’34 Act cases have to be brought in federal court.

Most circuits, such as the Second Circuit, take the position that ’33 Act suits – which includes Section 11 claims – must also be brought in federal court. The statutory language, however, is unclear. As a consequence, some courts have reached the opposite conclusion.

More specifically, California state courts as well as federal courts in the Ninth Circuit have concluded (in light of Luther v. Countrywide Financial Corp.) that Section 11 claims can be properly brought in state court. Indeed, when attorneys for Terraform Global tried to remove a ’33 Act case to federal court, the federal court not only sent the case back to state court, but also reprimanded the defendants’ attorneys and sanctioned them with plaintiff attorneys’ fees.

Knowing that these cases will stay in state court with its numerous advantages, plaintiffs have flocked to file Section 11 cases in California state courts.

The advantages of state courts are significant for plaintiffs:

- Compared to federal court, plaintiffs in state court are much more likely to survive defendant’s efforts to dismiss the case, even with relatively weaker pleadings. Typically, 32 percent of class action securities complaints are dismissed in federal court. Comparatively, in the last five years, only two Section 11 cases have been involuntarily dismissed in a California state court. (There were an additional three voluntary dismissals in state court where the federal case settled first, and the plaintiffs from the state court case joined the federal settlement.)

- The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA), which was enacted to address perceived abuses in securities class actions, is not applicable to state court cases. Since the PSLRA does not apply, discovery continues (and can lead to skyrocketing costs for defendants) while the court considers whether or not to dismiss the case. In federal court, discovery only begins if the case isn’t dismissed.

- Plaintiffs’ attorneys may have much more control over their case in state court given that they may be representing less sophisticated plaintiff shareholders. When there are multiple Section 11 cases against the same defendants, these cases are consolidated on an ad-hoc basis in state court, allowing plaintiffs’ attorneys to jockey for position. In federal court, by contrast, the plaintiffs’ attorney representing the greatest economic interest will typically become the lead plaintiff. This often means that the plaintiff shareholder is not an individual but is instead a sophisticated institutional investor—which is to say a real client.

- California state courts are perceived as friendly to plaintiffs. California courts have a reputation for lenient pleading standards, permissive procedural codes, and a receptive judiciary when it comes to securities class action suits.

Given these factors, not to mention the cost of litigation coupled with the strict liability standard for companies, it’s no surprise that companies are attempting to settle these claims as quickly as possible.

The settlements are significant, as you can see below. This 5-year settlement data extract comes from the D&O Databox, Woodruff Sawyer’s proprietary database of D&O litigation:

Image source: Woodruff Sawyer’s D&O Databox

Although this is a California state court problem, the impact isn’t limited to companies headquartered in California or with board members who live in California. For example, Alibaba (a China-based company) and King Digital (an Irish Company) both have Section 11 suits pending in California state courts.

Woodruff Sawyer’s review of the cases reveals that the plaintiffs are experimenting with a variety of potential jurisdictional anchors for California state courts, such as roadshow meetings in California to solicit IPO investors from California. All of the cases also mention that the IPO investment bankers have offices in California.

Parallel Section 10(b) Cases

It’s unclear what, if any, settlement pressure Section 11 cases in state court have on parallel Section 10(b) cases filed in federal courts. It seems unlikely that, where the class members and/or class periods overlap, courts would approve of double-dipping by plaintiff shareholders. However, where a Section 10(b) claim has legs and has survived multiple motions to dismiss in federal court, new dynamics may come into play when it comes to settling both the 10(b) and the Section 11 claims. More data is needed to fully understand these dynamics.

In the last five years, there were four companies with parallel proceedings in state court that settled in federal court. The federal court ultimately settled both Section 11 claims under the ’33 Act as well as Section 10(b) claims under the ’34 Act. Their counterpart Section 11 state court cases were then voluntarily dismissed.

Should IPO Companies Panic?

If a company has business reasons for its IPO, it should—of course—continue with the IPO process. Section 11 claims are worrisome, but there is no reason to panic.

Unlike M&A litigation, which, in its heyday, saw nearly 100 percent frequency (it’s lower now), Section 11 suits can only be filed against companies whose stock price drops below their IPO offering price.

It’s also worth observing that, unlike typical Section 10(b) federal securities class action lawsuits, we haven’t yet seen a rash of companion derivative suits. Fewer suits are clearly better than more suits.

What about companies that went public less than three years ago?

Ideally, your stock never falls below your IPO price within the first three years. If that happens, however, you are likely to be sued in California state court if plaintiffs can find a way to do so.

Mature public companies—those that have been public for a long time—have a very different risk profile for Section 11 suits for two reasons. First, mature public companies are not at risk of suits based on their IPO S-1 registration statement given the three-year statute of limitations. Second, stand-alone Section 11 claims against mature public companies are difficult for plaintiff shareholders to win because Section 11 requires that the plaintiffs be able to trace their shares back to the offending registration statement (in this case, a non-IPO offering). This is hard to do when there are a ton of non-IPO shares in the market.

D&O Insurance Carriers Respond

D&O insurance carriers that insure a lot of IPO business are exactly the carriers that IPO companies want to use. The underwriters at these carriers have a wealth of experience on both the underwriting and claims sides of the house and can be true partners to IPO companies when it comes to mitigating risk.

It’s also the case that these high-quality carriers are aware of the data and are taking a hard look at their IPO books.

Given the litigation environment, premiums for IPOs and newly public companies are going up, as are their self-insured retentions (SIRs). A mature public company that’s the same size as a relatively new IPO company will enjoy lower premiums and SIRs than the IPO company.

Companies that face increasing pricing and higher retentions will want to do a full marketing of their D&O insurance program. The challenge will be to balance the lower prices that may be offered by some carriers with the higher prices that may be quoted by more established insurance market players offering as good (if not better) terms and conditions—not to mention experience at paying claims and staying with clients when the going gets tough.

What Now?

Summing up: Section 11 claims are concerning, but at least they are becoming more predictable.

If your company is contemplating an IPO, you will want to go into the situation eyes wide open vis-à-vis the litigation risk. Working with experienced outside counsel and insurance brokers skilled at handling IPOs (and IPO-related claims in California state court) is more important than ever.

Consider too that when a company goes public, there is always a focus on important items like accounting controls and forecasting. The current litigation landscape for IPO companies warrants putting additional focus and resources into these and other elements that tend to help a company avoid surprising the financial markets with bad news.

If your company has recently gone through an IPO, whether or not it has been sued, have a conversation with your outside counsel and insurance broker to assess your company’s risk and develop a strategy for your D&O insurance renewal.

While the bad news is that there are a lot of suits, the good news is that we now have quite a bit of data about them. When it comes to risk management, knowing that there’s an issue, and being able to calibrate the issue, puts you way ahead of the curve.

This article was co-authored by Donna Moser and Vysali Soundararajan.

Authors

Table of Contents