Blog

Strict Liability Energy: IPO Litigation and Risk Management

| IPO companies are sued more frequently than mature public companies for many reasons. In this week’s D&O Notebook, my colleague Walker Newell focuses on why “registration statement” or Section 11 liability is the gift that keeps on giving to the plaintiff’s bar. He also outlines some classic fact patterns to help you understand how you can mitigate your risk of being sued, or at least make the suit go away faster and for less money. – Priya Huskins |

Imagine that you are a startup founder and CEO. You toil for years in the hot sun, painstakingly cultivating your business as it grows from a vulnerable seed into a promising sapling. It’s grow or die. You grow.

Now you want to transform your business into a mighty oak. To do this, you need more capital. And, because you have created an awesome business and because you are in the United States, you have the privilege of accessing the deepest, safest, and most liquid public securities markets in the world.

As you ring the Nasdaq bell, your son at your side, a small tear gathers in the corner of your eye. The stock doubles in the coming days. Your hard work has paid off. You’ve made it.

Fast-forward to a year later. You have continued to diligently tend your plot, but you have learned that reaching the next stage of development is even harder. You are experiencing growing pains; you miss your ambitious targets. Your stock price starts to fall and ultimately it falls below your IPO offering price.

A few weeks later, your lawyers report some bad news. Investors are banding together in a class action to accuse you of securities law violations. But you didn’t do anything wrong! You spend 16-hour days doing everything you can to make the business succeed and deliver returns for investors. You certainly didn’t intend to commit fraud or mislead investors in any way.

You may have gotten a bit out over your skis, sure, but there’s no way some poorly phrased language in your SEC filings could translate into legal liability, right?

Wrong.

IPO Companies Are Vulnerable to Securities Litigation

Companies are at their most vulnerable to securities litigation in the years just after their IPO.

Unlike in other areas of securities litigation, to win one of these cases, shareholders don’t need to show that you meant to trick them. They just need to show that you said something to investors in your registration statement that was: 1) material; and 2) false or misleading.

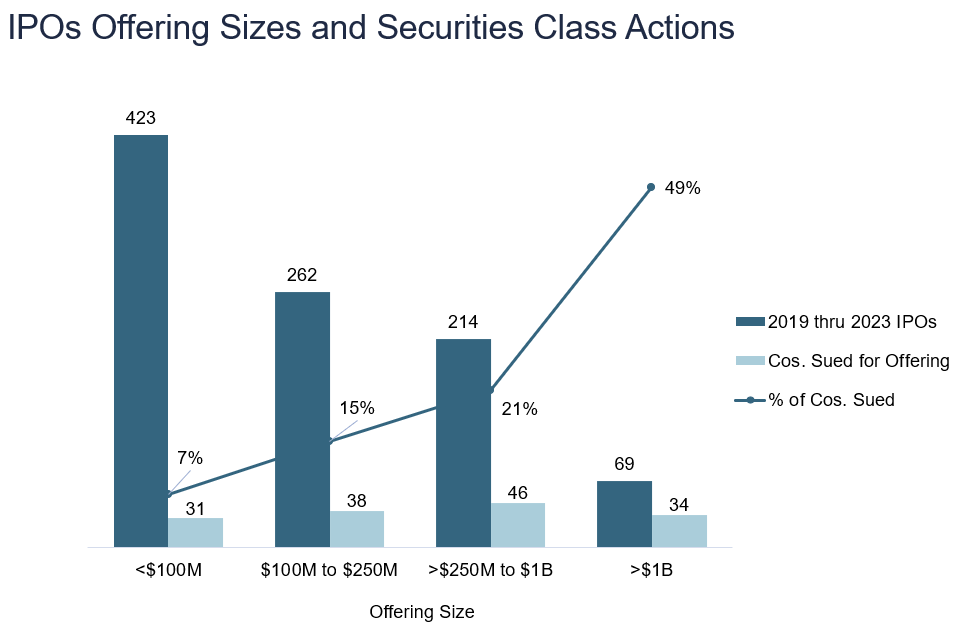

Plaintiffs’ lawyers are always happy to exploit soft targets. In recent years, between 1/4 to 1/3 of new public companies have been hit with some form of securities class action within five years of IPO. IPOs over $1 billion have a 1-in-2 chance of being sued.

In 2023’s moribund IPO markets, there were few new targets for the plaintiffs’ bar. But, as the capital markets show signs of unthawing in 2024, the next crop of fresh public companies will be ripe for the picking by plaintiffs’ lawyers.

Source: Woodruff Sawyer’s proprietary Databox ™

What lessons can we learn from the last wave of IPO litigation? If you can somehow avoid any meaningful dips in your stock price during your early years as a public company, you are a magical corporate wizard and I have nothing to teach you.

For mere mortals subject to fickle market forces, there’s no way to eliminate the risk that you will face IPO securities litigation.

Instead, you hope that if you are sued, it ends in a speedy dismissal, not an eight-figure settlement. To prepare for the worst-case scenario, you also need to have a carefully crafted D&O insurance program.

Strict Liability for Misleading IPO Registration Statements

Before we get to registration statements for IPOs (e.g., Form S-1 or F-1), let’s talk about the federal securities laws more generally.

The federal securities laws generally recognize that it would be unfair and unworkable to hold companies liable any time they say something that might be considered misleading.

To get sideways with the securities laws, you usually need to mess up in several ways at once by:

- Saying something material (i.e., reasonably important to investors)

- That is false or misleading

- With “scienter” (i.e., intent to commit fraud—or, in some jurisdictions, recklessness)

- That investors rely on, causing them to lose money

Section 10(b) Claims

The scienter/intent requirement is one of the biggest hurdles for shareholder plaintiffs suing under the central provision in the securities laws: Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

Thanks to the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (PSLRA), to get past the motion to dismiss stage, a shareholder trying to bring a 10(b) claim has to allege in specific detail—for each challenged statement—“facts giving rise to a strong inference that the defendant acted with the required state of mind.”

This is a significant barrier for plaintiffs. Thanks to this standard, plaintiffs can’t merely identify a possibly inaccurate statement and send a case straight into costly and invasive discovery.

This higher threshold is one of the reasons federal judges often throw out Section 10(b) securities class actions at the motion to dismiss stage (you have a better than 50% chance of winning your motion to dismiss or getting plaintiffs to withdraw a non-IPO securities class action case).

Section 11 Claims

Section 11 of the Securities Act of 1933 (not to be confused with its younger sister, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934) is a different animal.

Section 11 has no intent requirement. It says that your registration statement–the seminal document that you file with the SEC when you are going public (or are otherwise offering securities to the public, including a follow-on offering)—can’t contain any materially false or misleading statements.

If your filing contains any materially false or misleading statements and your stock price declines below the original IPO price when the “truth is revealed” about those statements, the company is liable. Full stop. (I’m simplifying a bit here, but this is basically the standard.)

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, a company’s liability under Section 11 “is virtually absolute, even for innocent misstatements.”

This strict liability standard is like catnip for plaintiffs. If they can convince a court that you may have made materially misleading statements, they can get to the costly discovery stage and begin turning the screws to drive a settlement.

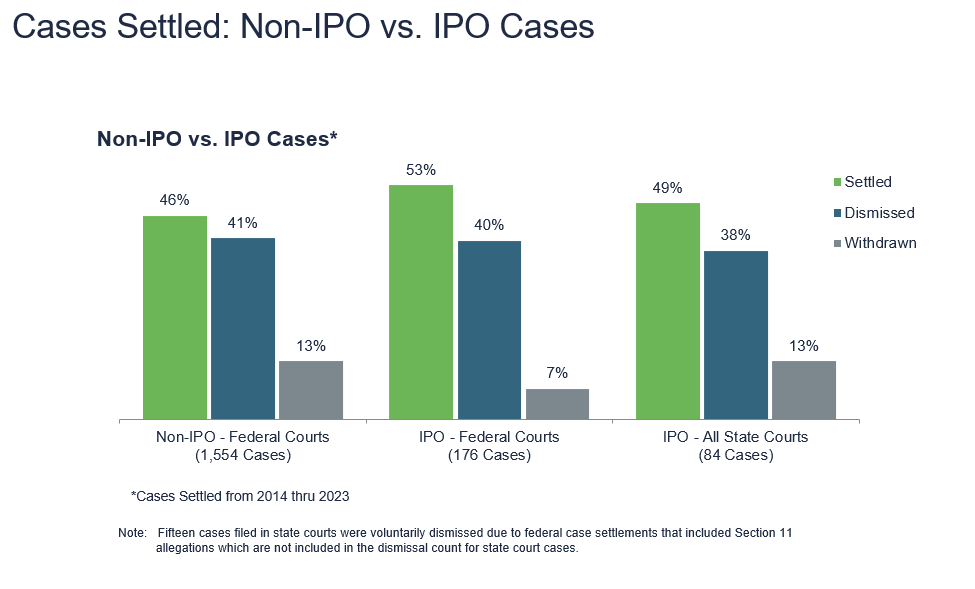

Remember how Section 10(b) cases are more likely than not to be thrown out at the motion to dismiss stage? The opposite is true for Section 11 cases.

Here, based on historical data, plaintiffs are more likely to win. And, as we have discussed in the past, the motion to dismiss is the critical moment that drives final outcomes in securities litigation.

Are you cursing the New Deal Congress for passing this zany 90-year-old law?

Here’s the good news: Even though plaintiffs have the upper hand, over the past decade, they have only won (i.e., reached a settlement in) 53% of IPO cases filed in federal court, according to Woodruff Sawyer’s proprietary DataBox analysis. You want to be part of the other 47% and get the case dismissed or withdrawn.

Source: Woodruff Sawyer’s proprietary Databox ™

IPO Litigation: Unfun and Unpredictable

A common theme in plaintiff Section 11 allegations is that in the lead-up to an IPO, a company and its insiders knew that things were going downhill fast. In these cases, plaintiffs claim that the company hid catastrophic known pre-IPO issues and foisted moldy common stock on an unsuspecting public.

If you have actual concrete knowledge that your company is definitely going directly down the tubes while you are in the process of going public and you still want to move forward with the offering, you should tell investors that you are definitely going directly down the tubes. Your IPO will be wildly undersubscribed, but at least you won’t have committed securities fraud.

Of course, in the real world, things are more complicated. Maybe you learn of significant government skepticism about the legality of your disruptive business, but you have no idea where the regulatory chips will ultimately fall.

Maybe you see a significant downtrend in your key metrics—which had been growing at a robust pace—in the six weeks immediately preceding your IPO, something that might be a temporary bump or that might presage a massive reversal, you just don’t know.

Maybe you learn that the vital enterprise customer who makes up 75% of your sales volume is thinking about dropping you for a different supplier but has not yet made a final decision.

If you move forward in the face of these uncertainties, and then it turns out your optimistic outlook was unwarranted, your defense lawyers should be able to raise a number of defenses.

One of these will be to point to your carefully crafted “Risk Factors.” This part of your registration statement will say:

- Our business may go down the tubes if [product issue x], [regulatory problem y], or [strategic blunder z] transpires;

- We can give no guarantees that these issues won’t happen and indeed they very well might happen;

- So: caveat emptor.

Source: “Blondie: comic strip, distributed by King Features Syndicate.

Plaintiffs will then respond that it’s misleading to say something awful might happen when it is actually happening at that time.

Plaintiffs will not yet have access to your emails or internal documents to show the judge that the awful thing was not just a risk but was actually happening. (Plaintiffs get access to these things through the discovery process, which only happens if they can get past the motion to dismiss stage.)

Instead, plaintiffs will rely on information in the public sphere and anything they can get by recruiting “confidential witnesses” (disgruntled current or former employees).

Plaintiffs will put whatever they have in an opposition brief to your motion to dismiss the case. Then it will be up to the judge to figure out whether plaintiffs have said enough things to make a plausible case that your registration statement contained at least one materially misleading statement. Again, this is basically a coin flip, with plaintiffs historically holding a slight upper hand.

What causes federal judges to dismiss some Section 11 cases and let others slip through?

Here are a few things to think about:

- What judge did you draw? Some judges are plaintiff-friendly; others are not. Some judges are very careful and diligent and will give both parties a fair shake. Others….

- How bad was your stock drop? Once you are past a certain undefined materiality threshold (let’s say ~5% to keep it simple), the size of your stock drop shouldn’t matter as a technical matter of law at the motion to dismiss stage. But, as a proxy for how bad your issues are and how much the market was mispricing your stock, it probably does matter.

- Did the market have a momentary freakout over one press release, or are you facing an ongoing corporate crisis? Again, this shouldn’t really matter. A judge can’t go out and do personal research about your company and then incorporate that research into her decision-making. But atmospherically, I think this does matter.

- Did you and your lawyers include accurate disclosure about any headwinds that you were facing in the lead-up to the IPO? Did you characterize big problems that had already materialized as hypothetical “risks”?

Section 11 Examples

Let’s look at a couple of recent examples of Section 11 questions that made it past the motion to dismiss stage.

Lyft

In 2022, Lyft agreed to a $25 million settlement to get rid of shareholder IPO litigation. Why did the company settle? Probably because the court denied Lyft’s motion to dismiss.

The key allegations related to customer claims of sexual assault by Lyft drivers. Trying to get these allegations kicked out, Lyft pointed to its disclosures around various “personal injury” and “trust and safety” issues, litigation, and risks.

But the judge didn’t find the phrase “sexual assault” anywhere in Lyft’s registration statement. That turned out to be a $25 million mistake (most of which presumably would have been covered by Lyft’s D&O insurance policy).

SmileDirectClub

Soon after its 2019 IPO, the orthodontia disrupter SmileDirectClub began facing down a scandal involving the safety and effectiveness of its products, and its stock price declined significantly below the initial offering price.

Shareholders sued and a federal judge allowed the case to progress past the motion to dismiss stage. (The company later filed for Chapter 11; shareholder plaintiffs are now fighting in bankruptcy court to preserve their potential rights.)

The most interesting part of the motion to dismiss ruling—and a recurring theme in Section 11 litigation—was related to intra-quarter financial trends.

SmileDirectClub accurately reported its historical financial information in its registration statement. But, during the quarter in which the IPO took place, earnings ended up taking a big hit.

However, the company didn’t know the final numbers at the time of the IPO, which was completed two weeks before the quarter ended.

As everyone knows, under normal circumstances public companies are only required to disclose financials on a quarterly and annual cadence. And for good reason.

But, according to some judges—including the judge who decided the SmileDirectClub case—you might have a duty to disclose intra-quarter financial information in registration statements under some circumstances (other judges have disagreed). If you do have to disclose intra-quarter financial information, under what circumstances? This remains quite murky. If you are seeing negative intra-quarter trends in the weeks leading up to your IPO, talk to your counsel.

The takeaway? Section 11 litigation is unpredictable and should continue to be a rich vein for plaintiffs. That’s why new public companies have to take the purchase of their D&O insurance so seriously.

Risk Mitigation for Upcoming IPOs

Managing your litigation risk through careful disclosure is something that you should absolutely do as you work through your registration statement with your lawyers.

No matter the strength of your disclosures, though, if you have a large stock drop below your IPO price in the first three years of life as a public company, there’s a good chance you will be slapped with a Section 11 lawsuit.

When this happens, if you have appropriate D&O insurance coverage, you should be fine. If you are underinsured or if there are other gaps in your insurance program, you may be in for some pain.

During the hard D&O market of recent years past, D&O insurance for companies preparing to IPO was very expensive. Today’s softer D&O market, with more capacity and fewer IPOs, has produced better pricing.

When the IPO market begins churning again in a real way, we will have a close eye on the pricing environment. Regardless, it will remain more expensive and complicated to insure new IPOs than mature public companies given the more difficult risk profile of new public companies.

You’ll want to work with data-driven insurance advisors who are experts in placing D&O for IPOs.

Author

Table of Contents