Blog

Climate Disclosures: A Tough Ask for Many Corporations

Climate disclosures are at the center of many discussions in boardrooms of corporate America—especially after the recent publication of BlackRock's annual letter from CEO Larry Fink.

These types of disclosures are difficult to make, leaving some corporations paralyzed as they try to navigate through the guidelines and pressures of doing so.

However, there are some initial steps that any company can take to make climate change and sustainability disclosures a regular part of their corporate governance process.

What Are Climate-Related Disclosures?

Climate-related disclosures aim to analyze and report a company's financial or operational risks related to climate change.

Today these disclosures are largely voluntary, and several independent organizations have provided frameworks for companies to use when making these types of disclosures. Having said that, there are some mandatory disclosures for companies in the US and abroad.

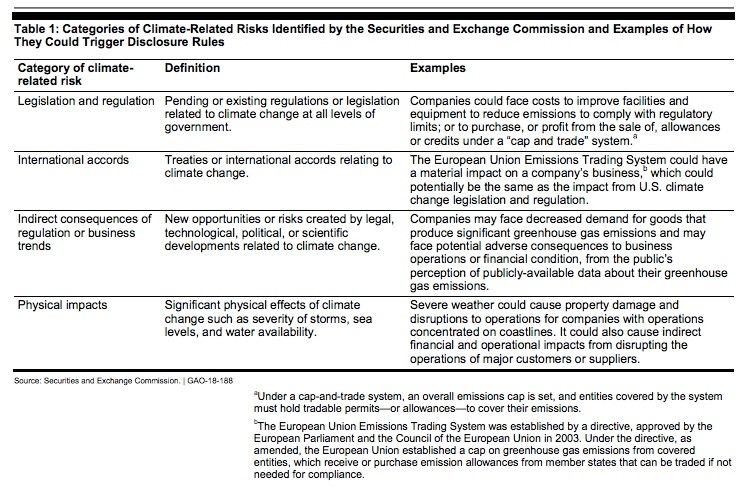

In 2010, the SEC issued interpretive guidance for public companies on what scenarios might trigger climate-related disclosures.

[caption id="attachment_22503" align="alignnone" width="745"] Image source: "Climate-Related Risks, SEC Has Taken Steps to Clarify Disclosure Requirements," United States Government Accountability Office[/caption]

Image source: "Climate-Related Risks, SEC Has Taken Steps to Clarify Disclosure Requirements," United States Government Accountability Office[/caption]

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) is another organization, founded in 2011, that works to implement climate-related financial reporting standards.

Newer to the scene and gaining influence (though still voluntary) is the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), of which BlackRock—the world's largest asset manager—is a founding member.

In 2017, the TCFD issued its initial recommendations for disclosure. Its goal: to "develop recommendations for voluntary climate-related financial disclosures that are consistent, comparable, reliable, clear, and efficient, and provide decision-useful information to lenders, insurers, and investors."

This year, BlackRock urged corporations to make "SASB- and TCFD-aligned disclosures, and as expressed by the TCFD guidelines, this should include the company's plan for operating under a scenario where the Paris Agreement's goal of limiting global warming to less than two degrees is fully realized."

The Paris Agreement piece is particularly interesting given that the US pulled out of that agreement in 2017. As we are seeing more and more, BlackRock as an investor is taking political matters into its own hands.

BlackRock Takes a Stand on Sustainable Investing

Early in 2018, Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, published a startling letter stating that corporations should not only maximize shareholder value but also do things that more generally benefit society. (Read more about that here).

Two years later, Fink's annual letter once again focused on change—this time climate change. In January 2020, Fink asserted climate risk was an investment risk:

As a fiduciary, our responsibility is to help clients navigate this transition. Our investment conviction is that sustainability- and climate-integrated portfolios can provide better risk-adjusted returns to investors. And with the impact of sustainability on investment returns increasing, we believe that sustainable investing is the strongest foundation for client portfolios going forward.

Fink is putting the money where his mouth is. BlackRock announced initiatives that would put sustainability "at the center of our investment approach, including: making sustainability integral to portfolio construction and risk management; exiting investments that present a high sustainability-related risk, such as thermal coal producers; launching new investment products that screen fossil fuels; and strengthening our commitment to sustainability and transparency in our investment stewardship activities."

This also includes no votes on proxies "when companies have not made sufficient progress" in the areas of sustainability.

In addition, Fink wants corporations to up their game when it comes to climate-related disclosures, including but not limited to sustainability: "This data should extend beyond climate to questions around how each company serves its full set of stakeholders, such as the diversity of its workforce, the sustainability of its supply chain, or how well it protects its customers' data."

Fink's ask isn't easy: these types of disclosures have been historically difficult. As I've written about in the past, disclosures around environmental, social and governance issues (ESG) are complex.

This is largely due to a lack of consistent, industry-wide standards for measuring and reporting ESG issues. Though a number of third parties are working to address this, it is still broadly uncharted territory.

As this article at Harvard Business Review argues, "Larry Fink isn't going to read your sustainability report":

If Fink is correct in predicting that capital will increasingly be allocated to those companies with the most sustainable business models, then investors will need new sources of data to understand and anticipate the economic significance of sustainability strategies.

This means that companies will need to communicate very differently with their investors. Disclosing their performance on the most material social issues (determined by the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board) as Fink recommends, is a necessary step.

But the more fundamental question is whether a given business is positioned to thrive in a future world transformed by climate change and financed by investors who care about social impact. And if that message is to be heard by the capital markets, it will have to come through financial statements, quarterly earnings calls, and investor briefings—not sustainability reports.

Six Things to Consider Regarding Climate Disclosures

Corporations that wish to better their disclosure on climate change and sustainability issues can take some basic steps towards doing so.

- Determine what disclosures your company is already making about climate change. Review your company's SEC filings, website, and official Corporate Social Responsibility reports. Also check out the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), which hosts data on public companies that have made disclosures regarding their carbon footprints. You can also go to "sustainability" or "corporate responsibility" groups internally to find out what kinds of disclosures have been made to the public, including by your marketing group.

- Understand what kinds of voluntary climate-related disclosures might be appropriate for your company. As mentioned previously, many organizations are working to standardize disclosures. Reviewing the disclosures of your competitors, as well as looking to some of the guidelines established by groups like SASB and TCFD can be helpful.

- Initiate discussion in the boardroom. Determine what level of commitment, if any, is appropriate for the company regarding climate change and environmental issues. These discussions may fall within a board's fiduciary duty obligations. In addition, good documentation of these conversations will be helpful to a board's defense when faced with litigation. (I will elaborate on this in a future post.)

- Think about measurement. Even if your company doesn't plan on disclosing soon, it's still wise to start the process of measuring the company's "carbon footprint." Keep in mind, however, that you may become obligated to disclose the results. Consider forming or hiring a group to take charge of these issues if none exist.

- Work with experts on disclosures. When making voluntary climate change-related disclosures, be sure to work with attorneys, accountants, and environmental experts to make sure those disclosures are accompanied by appropriate caveats and specific information about methodology.

- Consider incorporating climate-related information into risk factors. Even if you don't disclose, this will increase the likelihood that if sued your company will fall within the safe harbor that applies to forward-looking statements that are accompanied by meaningful risk factors.

Some boards might lean towards no or minimal climate and sustainability-related disclosure based on the view that these matters are more political than they are issues that fall within the realm of a serious business discussion.

This is a viable view right up until the moment major shareholders start asking for these disclosures—and some shareholders have definitely started to ask.

Of course increased disclosure inevitably leads to increased litigation risk, something I will discuss in next week's post.

Author

Table of Contents